On the night between Thursday

2nd and Friday 3rd March, 1944, in a railway tunnel

on the Battipaglia-Potenza line, in Italy, located between Balvano-Ricigliano

and Bella-Muro Lucano stations, in the region Basilicata, hundreds

of 8017 train passengers died, suffocated by the smoke of the

locomotives, in one of the most serious railway accidents in history,

the most serious to occur in Italy. The US Army 727th

Rail Operations Battalion Activity Report,

published in 1948, comments on the accident: "Probably

never in the history of railroading has there been a catastrophe

such as occurred at Balvano".

The strong discrepancies in the number of victims between the

different sources and the difficulties in burying hundreds of

bodies in a very limited time and space make it credible that

the number of victims was higher, even much higher, than the body

count or the number of missing people. from train 8017, reported

by his relatives. The number of six hundred victims appears anything

but improbable and part of the very numerous missing persons of

the period could have been among the casualties of the Balvano

disaster, if not killed in war, under bombings, from illnesses

or in accidents or attacks, which commonly occurred in that age.

The preconditions

for the tragedy

In March 1944 southern

Italy had been liberated, the Nazi-fascists had fled to the north,

the front was stopped on the Garigliano river and the battle of

Cassino was underway, with the destruction of the Montecassino

abbey on 15 February. Naples was liberated with the Four Days

Revolt (27-30 September, 1943), while Potenza was liberated on

22nd September, 1943 (Barneschi, 2014). However, the devastation of

the war and the limitations on trade imposed by the Allied Forces

left the city's population in a state of extreme poverty, and

the lack of food literally led many people to starvation. The

only resource for the population of Naples and the coastal area

was to look for food where it was still found, in the countryside,

bartering it with the few objects left at home. So many set out

on foot towards the hinterland, or they relied on the very few

carts or motor vehicles, or even on train 8021, which connected

Naples to Bari, via Potenza and Taranto, with a journey that could

even last 24 hours, in program only twice a week, on Wednesdays

and Saturdays (Barneschi,

2005), and which was

consequently overloaded.

Twenty days before the tragedy, on 13 February, 1944, Giovanni

Di Raimondo, Undersecretary of State for Communications for Railways,

Civil Motor Vehicles and Transport under concession of the Badoglio

government, who later became Director General of the State Railways,

in a letter to the State Railways Department heads of Naples,

Bari and Reggio Calabria and, for information, to the Cabinet

of the Presidency of the Council of Ministers and to various ministries,

referred to the bi-weekly Bari-Naples train via Potenza, explaining

that "it has proven to be absolutely insufficient with

respect to the needs of the large population of the regions crossed.

The train itself is assaulted by an overwhelming crowd of travelers

who wait for a long time in the various stations, especially between

Metaponto and Battipaglia". Consequently Di Raimondo

asked for a daily train, or at least three times a week. In reality

the allied authorities, in the person of Colonel Charles F. Dougherty,

had already made it clear on January 26 that due to military needs

it was not possible to increase the frequency of the train

(Restaino). The only remedy from the Allied

authorities was instead a blunt, often violent, repression of

the access of passengers on freight trains, and an unloading of

responsibility on the Italian authorities, with the request for

a mass of controls that were impossible to carry out.

As a matter of fact, for safety reasons, the Allied authorities

had set a maximum number of tickets for each train, moreover requiring

the possession of an authorization to travel. Anyway, the mass

of people trying to move, driven by hunger, was pressing. Many

travelers were therefore unable to find a place on passenger trains,

and the alternative was to board, as illegal passengers, however

tolerated, and often equipped with a ticket, on the freight trains

that travelled along the line to Potenza. Train 8017, the one

involved in the tragedy, operated on the same route on a non-regular

basis, as an "OL" ("Orario Libero") train,

i.e. at free schedule, and was used for the transport of weapons,

ammunition and materials for use by the Allies, and was therefore

under their control, although it was operated by Italian railway

crew and rolling stock. All this even if a part of the Allied

territory, including the area of the accident, should have returned

under Italian sovereignty on the basis of a decree of February

1944 (Martucci).

Journeys on these trains, as well as being difficult, were also

dangerous for the safety of the passengers,

who often traveled clinging to the outside, as reported in La Domenica del Corriere

of 3 October, 1943, or with legs astride on the buffers, on coal

tenders or on the imperial (roof) of the carriages, risking being

crushed between the train and the tunnels vault if they didn't

quickly lie down. Furthermore, it happened that entire carriages

were emptied to make room for the Allied soldiers (Barneschi, 2005).

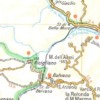

Balvano

The town of Balvano

is located in the province of Potenza, in Basilicata region, in

Italy. On 1st January, 2023, 1,726 people lived

there, while in 1936 the inhabitants were 2,481 (Istat.it). Balvano lies at the border with the province

of Salerno, in Campania, at 425 m (1,394 ft) above sea level.

The town was seriously damaged by the earthquake of November 23,

1980, which made 77 victims, and was completely rebuilt in the

following years. Starting from 1987 a confectionery industrial

plant of Ferrero operates in Balvano territory.

The railway

line

The Naples-Bari

line is essential in the transport of travelers and goods between

the Tyrrhenian and Adriatic coasts. It is divided into several

stretches with junctions in Salerno, Battipaglia, Potenza,

Metaponto and Taranto. The Battipaglia-Potenza-Metaponto stretch

was built between 1863 and 1880, it was under the responsibility

of the State Railways from 1905 to 2001, and is still single track.

The Balvano accident occurred in the Battipaglia-Potenza

stretch, which, after the initial course on plains or low hills,

climbs up the Apennines, and in particular in the segment between

Balvano and Baragiano it runs almost continuously uphill, along

the meanders that the Platano stream

digs into the mountains. The torrential regime of the Platano

causes sudden floods, one of which in 1929 swept

away twelve railway workers who were inspecting a tunnel,

killing seven of them.

The sloping profile for a long stretch of the line had caused

another serious accident: on 12 December, 1942, a troop train,

headed for embarkation for North Africa, which had originated

in Piacenza, set off from Potenza, traveling in the direction

of Naples, therefore going downhill. After the Tito station, at

792 m (2,598.43 ft) above sea level, perhaps due to a brake failure,

the train picked up speed and, after the Franciosa stop, at 522

m (1,712,6 ft) above sea level, after a run of almost 12 km (7.4

Mi), it broke into two parts, one of which went off the railway

track and crashed, causing 29 deaths and 150 injured (Barneschi, 2005).

Since 1959 the line has been served by diesel locomotives (Restaino), and only on 31 March, 1994,

just over 50 years after the disaster, it was electrified, after

eight years of closure for the necessary works (Barneschi, 2005).

Balvano

railway station

The last stop of train

8017 was Balvano-Ricigliano railway

station, which was also the place where the few survivors

able to walk headed, the reference point for the rescue operations

and the first shelter for the bodies recovered from the train.

The station, together with the

Romagnano-Balvano section of the line, was inaugurated on 3 June,

1877, and is located at km. 124,842 (77.57 Mi) from Naples, at

an altitude of 264 m (866 ft) above sea level, 2.7 km (1.67 Mi)

from the town. It was partially destroyed by the earthquake of

23 November, 1980 and entirely rebuilt.

Today it no longer has the status of a station but is a stop,

where only two trains stop per day for each direction, and is

not served by railway staff on site.

The tunnel

The entrance

of the "galleria delle Armi"

tunnel, is located in the municipality of Balvano, about 5 kilometers

(3.1 Mi) from the town center, near the border with the province

of Salerno (coordinates 40.66467728361175, 15.50313862651606).

The tunnel, 1,968.78 meters

(6,459 ft) long, with a gradient of 13 per mil, is the longest

of the 37 on the Battipaglia-Potenza section (www.antiarte.it), is located 1,791 meters (1.11

Mi) after the Balvano station, at km 126.633 (Mi 78.69), and takes

its name from the mountain under which it passes, Monte dell'Armi,

957 meters (3,140 ft) high. In turn, the mountain would take its

name from the arms hiding places created by the brigands who operated

in the area until the end of the 19th century, or from the medieval

Greek word armos, meaning "cliff" (www.antiarte.it). Restaino refers he heard it

called "de lu battaglione" ("of the battalion",

giving it a military meaning.

The tunnel is straight, apart from the final stretch which bends

to the right (coming from Balvano), runs in an "s",

and in the last segment is flanked by 37 large

windows (see plan, from

Restaino). Before the change of direction there is a service tunnel

that comes out into the open and serves as a ventilation duct,

although it is largely blocked by landslides. Neither the duct

nor the windows served to save the passengers of train 8017 from

suffocation, because the train stopped much earlier.

The class

476 locomotive

The 476 locomotives

were built between 1909 and 1918 in three different Austrian factories,

and were used by the Imperial-Royal Railways of the Austrian State

(KkStB, Kaiserlich-königliche österreichische Staatsbahnen)

with the code KkStB 80. At the of the First World War, 72 of these

locomotives passed to the Italian State Railways, because they

remained on the territory that had become Italian, or because

they were handed over by the Austro-Hungarians as war booty. In

turn, at the of the Second World War, some locomotives of the

476 group, which were located in the ex-Italian areas that passed

to Yugoslavia, were acquired by the Yugoslav railways with the

code JDŽ 28. The conduction,

i.e. the position of the driver, was on the right of the locomotive

(Barneschi,

2005). On train 8017

the specimen on duty was, according to Barneschi 476.023, based

on Wikipedia

476.058, Restaino and Raimo report 476.038, according to Canzoni

contro la guerra. A specimen, 476.073,

is located at the Railway

Museum of Trieste Campo Marzio (currently, March 2024,

the museum is closed).

The class

480 locomotive

The 480 locomotives

were built in 1923 in 18 specimens by the Officine Meccaniche

of Milan. The conduction was on the

left of the locomotive (Barneschi, 2005). They had five coupled axles, a maximum

speed of 60 km/h (37 mph) and were designed to work on the Brenner

railway, which became Italian after the First World War. With

the electrification of the Brenner line in 1930, some locomotives

were transferred to the depots of Catania and Messina and six

engines were sent to the Salerno depot, including 480.016,

in service on train 8017, which in 1966 was still in service at

the Catania locomotive depot. Another specimen, 480.017,

can be seen at the National

Railway Museum of Pietrarsa, near Naples.

The crew

On the 480.016 the

engineer was Espedito Senatore and the stoker Luigi Ronga, who

was the only one of the crew of the two locomotives to survive,

as he fainted and fell on the roadbed, finding a little more oxygen

at ground level, enough to make him survive (Pocaterra). The engineer Matteo Gigliano, 55, from

Salerno, and the stoker Rosario Barbaro, 31, from Torchiara (province

of Salerno) (Martucci) served on the 476.023. The train

manager was Luigi Ventre from Cava de' Tirreni (Salerno), the

head controller was Domenico Sessa, 43, from Pellezzano (province

of Salerno), the controller was Vincenzo Cuoco, 45 years old from

Benevento and the brakemen were Roberto Masullo and Giuseppe De

Venuto. There were also, as workers acting as brakemen Michelangelo

(or Michele) Palo, Giuseppe Scarcella and Gaetano Sgroia aged

34. Also on board, but not on duty, were brakemen Onofrio D'Ambrosio,

21, from Ricigliano (province of Potenza) and Paolo delli Carri,

49, from Benevento. Only Ronga, Masullo, Scarcella, De Venuto

and Palo survived (Barneschi,

2005).

The journey

Freight train 8017

left Naples in the early afternoon of March 2, 1944, headed to

Catanzaro, via Potenza, the only possible line, given that the

Tyrrhenian line was impassable due to Allied bombing (Barneschi, 2014). The train was bound to load

wood intended for the restoration of bridges destroyed by the

war, and was initially made up of 23 empty wagons and one service

wagon (Barneschi,

2005). Even though

the train was almost completely empty, six carriages were not

sealed and were occupied by unexpected passengers.

The train was hauled by an E626 electric

locomotive (Raimo), but, given that the line from

Battipaglia to Potenza was not electrified, a steam locomotive,

type 476, came

into operation in Salerno. The train left Salerno at 5:15pm (see

the graphic representation of the

journey), and along the way it became loaded with passengers.

After 74 km (46 Mi) from Naples, shortly after 6:00pm it reached

the Battipaglia station, where, before the beginning of the sloping

railway, locomotive 480,016 was joined in front of the train,

but 24 more freight wagons were also added, bringing the total

number to 48. Again in Battipaglia, the Allied military police

violently cleared the train of stowaways, but many of them immediately

got back on, and the train set off again overloaded. In Persano

two wagons were discarded and in Sicignano one more was excluded,

so at 0:12am the convoy arrived in Balvano, with 45 wagons, and

set off again at 0:50, passing through the first short

tunnel immediately after the station, then a bridge

over the Platano, then two other tunnels, while the railway line

gradually increased its gradient, and at the fourth tunnel, the

delle Armi, the speed was extremely

reduced, until, after 500 meters (1,600 ft) from the entrance

to the tunnel, the train stopped.

The tragedy

Train 8017 found the

tunnel already saturated with smoke, left by the locomotive of

the previous train, 8013, which had passed about an hour earlier.

Stopping about 500 meters (1,600 ft) from the entrance of the

tunnel, probably due to various contributing factors, which added

up by fate, it only managed to retreat about 200 meters (650 ft),

allowing the people who were in the rear carriages to exit the

tunnel and save themselves. The other people, who remained in

the tunnel, almost all died suffocated by carbon monoxide, produced

by the incomplete combustion of bad quality coal, perhaps worsened

by the introduction of coal from the tender

before entering the tunnel, a practice prohibited as it is dangerous,

due to the strong release of toxic gases from the coal just put

in the boiler. Many of the passengers were stunned, almost without

realizing it, others were asleep, and passed imperceptibly from

sleep to death, without having the possibility to react or be

afraid, as evidenced by the relaxed position in which their bodies

were found by the rescuers.

News of

the accident arrives

The station manager

of Balvano, Vincenzo Maglio, who had given the departure signal

to the train, should have received from the station manager of

the next station, that of Bella-Muro, at km. 132.600 (82.40 Mi)

(7.758 km, 4.82 Mi after Balvano) the telegraphic notice that

the train had arrived. Not having received the telegram, he was

not initially worried, thinking of a delay due to the many factors

that delayed the progress of the trains, and sometimes required

a travel time of two hours (Caggiano),

and went to sleep, taken over by the deputy stationmanager Giuseppe

Salonia. The latter received from Ugo Gentile, deputy stationmanager

of Baragiano-Ruoti, a request for news on train 8017, which had

not arrived, and at 2:40-2:50am he was reached by a call from

the stationmanager of Bella-Muro. So, he took action to someone

to reconnoiter the line. At around 3:00am the telegrapher of the

Potenza station, Luigi Quaratino, received a message from the

Baragiano station reporting that train 8017 was "stopped

on the line between Balvano and Bella Muro due to insufficient

traction force, awaiting help".

A rescue locomotive left Potenza shortly after 5:00am, and at

5:10am one of the brakemen of the 8017 train, perhaps De Venuto

(according to some sources Palo), who was in one of the rear carriages,

those who when the train he stopped, remained outside the tunnel,

returned on foot to Balvano to raise the alarm. With him, about

a hundred passengers from the rear carriages of the train had

been saved (Barneschi,

2005).

At 5.30am from Balvano station, the locomotive of train 8025,

the one following 8017, left to rescue, and arrived at the galleria

delle Armi tunnel at 5.40am. The rescuers began to notice the

large number of corpses and, among other things, they noticed

that the locomotives were both still under pressure. The people

still in the tunnel who showed signs of life were rescued, then

train 8017 was towed back and, according to the testimonies collected

by Barneschi (2005), the bodies found along the tracks

were mangled by the wheels of the train itself. Train 8017 arrived

at Balvano station at around 8.15am, and from the train

parked at the station the recovered

bodies were lined up on the platform

of Balvano station, and then loaded onto trucks

requisitioned for the occasion.

Balvano's medical officer, Orazio

Pacella, intervened to reanimate the survivors, giving them

injections of adrenaline into their hearts, trying not to make

mistakes, and to choose only people who were still alive, given

that he only had one hundred vials of the drug. After saving 51

lives, he was removed from rescuing the survivors by the allied

doctors, who had arrived in the meantime, and he was prevented

from saving other people (Mussa).

The Carabinieri police of Potenza and the Fire Brigade of Salerno

and Naples also intervened, with the speed allowed by the state

of the roads and the lack of supplies.

The corpses were taken to the Balvano

cemetery, but due to lack of space they were temporarily buried

in four mass graves near the cemetery, for over four hundred bodies.

The land was offered free of charge by Francesco Di Carlo from

Balvano, who died of a heart attack the day after his act of generosity

(Barneschi,

2005). Many of the

victims did not have documents, which perhaps had been lost in

the frantic rescue operations for so many people. In the Balvano

cemetery, Salvatore Avventurato,

a petrol station owner from Torre del Greco, near Naples, had

a marble chapel built at his own expense in memory of the victims,

including his father, his brother and an uncle (Mussa).

Many of the bodies lined up at the station and in Balvano cemetery

were recovered by relatives, who had rushed over in the meantime,

and buried in the cemeteries of their places of origin. This is

one of the reasons for the discrepancy in the death toll between

various sources.

Railway traffic, at the pressing request of the Allied authorities,

resumed the day after the tragedy, on March 4 at 12:00pm. On 9

March, 1944 the Badoglio Government, based in Salerno, dedicated

the entire session to the disaster.

The victims

In the days immediately

following the tragedy, the newspapers reported tolls that varied

from 426 casualties in Il Messaggero, to 500 in Il Corriere

della Sera, to over 500 victims in La Stampa, 509 (the

next day 502) in La Gazzetta del Mezzogiorno. In the following

years, Nino Lo Bello in the Chicago Tribune Magazine, in

addition to Caggiano, Frisoli and Raimo reported 521 deaths, Martucci

reported 427 deaths, with the doubt that they were 521, Pocaterra

and Pepe over 500, the tombstone in the Balvano cemetery 509,

Barneschi (2005

and 2014) over 600.

The discrepancy is due to the large number of bodies to be buried,

combined with the lack of space available and the free initiative

of the relatives of some victims, who independently provided for

the burial of their loved ones.

The only "illustrious" victim was Professor Vincenzo

Iura, 65 years old, from Baragiano, professor of surgical pathology

at the University of Bari and surgeon at the Civil Hospital of

Potenza (Pepe). From the list of 434 names cited

by Restaino it is clear that the victims were almost all from

Campania (87.3%), from the provinces of Naples (54.8%) and Salerno

(31.3%), with a particular concentration in the Vesuvian area,

with 81 of the victims coming from Resìna (today Ercolano)

and many others from Torre del Greco (27), Castellammare di Stabia

(25), Portici (17), Boscoreale (14), Boscotrecase (13), Torre

Annunziata (10), and, for the province of Salerno, many came from

Cava de' Tirreni (28), Nocera Inferiore (24) and from the Amalfi

Coast.

The causes

The Balvano accident

probably had various contributing causes, which were invoked by

the various parties involved and by the press, often according

to personal and institutional convenience and the needs of war

propaganda, given that the war was still ongoing and would have

ended, in Europe, just over a year later.

Many have succumbed to the temptation to present the tragedy as

the result of a dark conspiracy or, at the very least, as the

outcome of specific faults and responsibilities, of individuals

or institutions, then covered by silence and a willful oblivion.

We have seen how for other tragedies that occurred in the following

decades, the memory was kept alive only by a few, and in particular

by the relatives of the victims, and in case the oblivion was

aided by those who wanted to cover up deliberate acts, such as

terrorist attacks, while accidental tragedies, such as that of

Balvano, have often been forgotten because they were considered

fortuitous events, for which no one could be considered responsible,

or because the possible culprits were among the victims. Thesearch

for causes was certainly made less easy by the chaotic situation

of the time, with southern Italy set free but devastated by the

war and subjected to a harsh Allied government, often with punitive

connotations for the past belligerence with the Germans, in addition

to the presence of the front about two hundred kilometers away.

Here is a brief review

of the possible contributing causes of the Balvano tragedy:

Coal The poor quality of the coal used

by the two locomotives, of Yugoslavian origin, supplied by the

Allies, could have caused at the same time a lower thrust of the

engines, due to the reduced calorific value of the fuel, and poor

combustion, with the production of smoke with a higher carbon

monoxide content, in the first case contributing to the train

stopping, and in the second case saturating the tunnel with toxic

smoke. On the other hand, in March 1944 no other type of coal

might have been available: no longer the German coal from the

former allies, but not yet the Welsh coal from the new allies,

who reserved it for their own uses for the still ongoing war.

Lack

of air exchange The

tunnel runs straight for almost all its way, but in the final

stretch it bents almost at a right angle, due to the addition

of a section of artificial tunnel, made to protect the railway

from landslides. This shape, however, did not facilitate air exchange,

interrupting the flow between the two ends of the tunnel. The

poor breathability of the air was worsened by the stagnation of

smoke from the locomotives of previous trains, in the specific

case of 3 March, 1944 it was train 8013. For the railway workers

accustomed to working on the Battipaglia-Potenza line, the stagnation

of smoke in the galleria delle Armi tunnel was a well-known fact.

Precisely on the same line, in a tunnel between Picerno and Tito,

less than a month earlier, on 8 February, 1944, the engineer Vincenzo

Abbate, driving a 476 locomotive, had found himself in conditions

of asphyxiation and, to breathe better, he had raised the flippable

gangway between the locomotive and the tender, lying down on his

face, to better breathe the air of the layers closer to the rails.

However, he had fainted and his head had remained crushed between

the locomotive and the tender, and he had been killed (Barneschi, 2005).

Overloading Due to the poor quality of the

coal, the allied authorities, in particular the Military Railway

Service of Salerno, had given instructions not to load the trains

beyond 350 tons, which could be increased to 630 in the case of

double traction, even if there is no written trace of such provision.

The actual load of train 8017, after the Battipaglia station,

is unclear, and varies, deping on the sources, up to 520 tons,

with a length of 479.30 meters (157,250 ft) (Barneschi, 2005). In any case, the official load

of freight did not take into account the over six hundred passengers

who boarded clandestinely, whose weight can be estimated at over

40 tons. The shortage of trains in liberated Italy created a demand

for transport much greater than supply, and train 8017 was probably

overloaded, due to the excessive number of carriages and the weight

of hundreds of passengers.

Skidding The lack of thrust on the long

climb from Balvano to Bella was worsened by the strong humidity

of the tracks in the tunnel, due to the condensation of smoke

from the locomotives, to the low temperature of early March, and

to the dripping from the vault and walls of the tunnel, coming

from the circulation of water inside the mountain. The skidding

should have been contained by the release of sand on the tracks,

which perhaps did not happen or was not sufficient. Pocaterra

reports the story of a train driver from Bologna who in 1954 described

the frequent skidding of the 476 locomotives uphill in the tunnels

of the Calabrian lines, with the further difficulty of the hardness

of the throttle lever, which required two people to operate it.

Misunderstanding

among the railway crew

According to some,

the train's sliding backwards would have pushed the engineer of

the first locomotive to backtrack to exit the tunnel, but the

brakemen at the rear would have misunderstood, believing that

the sliding backwards was accidental, and would have tightened

their brakes, creating a stall, while the engines went at maximum

power, increasing the production of smoke. According to one of

the rescuers, the operator Mario Motta, no less than thirteen

cars had been braked (Restaino). The length of the train made

communication between the head and the rear impossible.

According to Raimo, the reversing lever of engine 480.016 was

in the forward gear position, while in the rear engine the lever

was placed in reverse position, which would have created a stall

due to the conflicting thrusts. However, the fact that the two

locomotives were driven from opposite sides made communication

between the two engineers difficult. According to Restaino, however,

still referring to the testimony of the operator Mario Motta,

both cars were set to reverse gear. According to Barneschi (2005), based on the inspection carried

out on the two locomotives when they were brought back to Balvano

station, the 480 was in reverse gear and the 476 was in forward

gear. It is not unlikely that, after the accident, the controls

were tampered with, or that untrue news was reported, to clear

oneself of possible involvement in the disaster.

Loss

of consciousness of the engineers Both

engineers died in the Balvano tragedy, so at a certain point in

the accident they will have lost consciousness, no longer being

able to intervene in any way on their respective engines. Furthermore,

the difficulties in operating the throttle lever, reported by

Pocaterra, would have been even greater for a driver on the verge

of suffocation.

The

allocation of passengers According

to the Allied commission of inquiry, the majority of passengers

"in consideration of the best protection from the weather"

were found in the front carriages of the train, those trapped

under the tunnel, while passengers placed in the rear carriages,

which remained outside the tunnel, and who were saved, were many

fewer (Barneschi,

2005).

The account

of the Americans

The above mentioned

report

on the activity of the 727th US Railway Operations Battalion

recounts the work of the military unit during war operations in

North Africa, Italy and France. The tragedy of Balvano is told

as something that had never happened in the past on a railway

line, which happened on 5th March, 1944 (in reality it was

two days before), due to illegal invaders ("trespassers")

who went to Bari, Brindisi and Taranto (the train actually ended

in Potenza), to get food, olive oil and other things from the

black market in Salerno, Naples and numerous other Italian cities.

There is therefore a strong negative prejudice against Italians,

seen as habitual violators of the law, without taking into account

the poverty and hunger caused by the war and, among other things,

by the Allied bombings. Furthermore, we seem to read a sort of

racist moralism, according to which the Italians, criminals or

at least undisciplined, had paid for their transgressions with

their lives.

The dynamics of the accident are traced back to the poor quality

of the coal, the locomotives slipping and overloading. The number

of victims is estimated at 508, and the report is careful to specify

that no American military personnel were involved. American investigators

would have interrogated many Italians involved in the incident,

especially railway workers working in the area. The investigation

gave no results and General Gray defined the tragedy as a fatality

("an Act of God"). In the meantime, a similar

accident had occurred near Baragiano, ten kilometers from Balvano,

with only one victim.

The Chicago Chronicle of 20 March, 1951, in reporting the

news of the summons from the Italian State by the victims' relatives,

gives different information: the newspaper wrote of 427 deaths,

of a journey south to load weapons and ammunition, and blamed

Yugoslavian coal, which quality was very poor.

The account

of the fascists

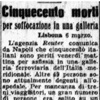

The first news of

the tragedy reached Italy occupied by the Nazi-fascists through

dispatches from Lisbon issued by the British Reuters agency. The

Milan newspaper Il Corriere

della Sera, published in the republican puppet state of

Salò, on 6 March in a short article summarily recounting

the incident, without specifying the location, reporting a death

toll of 500. On the same front page it reported 600 casualties

in the Allied bombings.

On March 7, the Turin newspaper La

Stampa reported the disaster, and the following

day published further details, and citing «serious

responsibilities of the "liberators"» reported

that on the train "militaries and civilians had been made

to travel" (sic) including numerous women and

children, and among the wounded there would have been English

soldiers. The newspaper of Rome Il

Giornale d'Italia of 7 March reported 501 deaths, locating

them generically in southern Italy, on a train heading east, while

Il Messaggero of

23 March, the same day of the attack in Via Rasella and of the

start of the retaliation of the Fosse Ardeatine (see my webpage

on it), published the news, referring of a toll of 426 "Italians",

also hypothesizing victims among the allied soldiers, maliciously

kept quiet. Il Messaggero was also and still is a newspaper

from Rome, at the time under Nazi occupation, even though it formally

had the status of an open city.

Similar

massacres

Accidents caused by

passengers and train staff suffocating due to smoke in tunnels

were not uncommon, although they often ended without casualties.

In the past, several accidents had occurred in Liguria, at the

end of the 19th century. In one of these accidents, on 11 August,

1898 at approximately 8.00pm, freight train 3132 left Genoa and

headed for Ronco Scrivia, crossing the Giovi tunnel, in the municipality

of Serra Riccò, in the province of Genoa. In the tunnel

the train remained uncontrolled due to the asphyxiation of the

crew, and rushed on passenger train 120 stopped at the Piano Orizzontale

dei Giovi station. The accident caused nine deaths, including

two children, and over one hundred injured, and triggered a series

of discussions, among other things on the quality of the fuel,

briquettes made of coal dust mixed with pitch and tar, produced

by the Carbonifera company of Novi Ligure, owned by the member

of parliament Edilio Raggio, who tried to oppose the replacement

of the briquettes with real coal from England. The legal proceedings,

however, were unsuccessful.

Memory

Two plaques have been

placed at the Balvano station in memory of the tragedy, one dated

3 March, 2017 and another

which refers to the event "San Mango-Balvano: percorso

di memoria e di futuro" ("San Mango-Balvano:

path of memory and future" jointly promoted by the Pro

Loco of Balvano and San Mango Piemonte (province of Salerno) to

remember the tragedy of train 8017.

The American country singer and songwriter Terry

Allen dedicated the song “Galleria dele Armi”

(sic) to the tragedy (listen on YouTube),

in his 1996 album "Human

Remains".

On March 3, 2004, on the 60th anniversary of the Balvano tragedy,

the Cyberassociation "Treno

di Luce 8017" ("Train of Light 8017"

was founded, with the task of bringing together the families and

friends of the victims of train 8017. The creators of the association

explain that "Il Treno di Luce is not only a material

convoy but a celestial means to remember all those dead, victims

of a useless holocaust, the result of war and of the so-called

civil life that overwhelms the poor. For this reason the Treno

di Luce wants to travel on the rails of Cyberspace to bring his

message of peace against the war and the oppression of the weak

by the strong.”

Legal

aftermaths

On 11 November, 1945

the investigating judge of the Potenza Court decreed the dismissal

of the case, at the request of the Prosecutor of the King's Office

of Potenza, as the fact did not derive from fault or fraud, being

due to the poor quality of the coal (Barneschi, 2005). In 1946 the Court of Potenza

initiated proceedings to identify possible criminal liability,

but on 18 December of the same year the proceedings were closed

and no culprits were identified. In the same 1946 Luisa Cozzolino,

Michele Palumbo's widow, who had lost her husband in the massacre,

brought proceedings to ask for damage compensation from the State

Railways. This request was followed by 300 more requests from

the families of the victims, and then the proceedings were reduced

to 41, because many families joined in, relying on the same lawyers.

The total compensation exceeded one billion liras. The defense

of the State Railways requested the dismissal because the railway

traffic at the time was under the responsibility of the Allies,

and it was "damage caused by the Allies as a consequence

of non-combat actions". Furthermore, the victims did

not have tickets, and therefore there was no contract between

the company and the passenger for transport. Finally, jurisdiction

over the matter fell to the court of Potenza, and not that of

Naples. The railway company appealed to the Court of Appeal of

Naples (Martucci). The trial began on March 28,

1951, and was the occasion for a resumption of media attention

on the massacre. The dispute ended with the payment of compensation

for civilian victims of war events, limited to those who could

show a ticket (Wikipedia).

Investigative

reports on the massacre

In the years following

the massacre, the weekly Oggi of 15 March, 1951, with an

article by Corrado Martucci, dealt with the resumption of civil

action proceedings for damages by the victims' relatives, recalling

the events of seven years earlier. In 1956, on 11, 18 and 25 March,

the weekly L'Europeo published an investigation in three

episodes by Giulio Frisoli, with a strong sensationalist slant

and with plenty of faults. On 25 May 1957 the Rome newspaper Il

Tempo published an article by Nestore Caggiano which recalled

the massacre, upon the resumption of proceedings for compensation

for damages before the Court of Appeal of Naples.

More than twenty years of silence followed, until Cenzino Mussa's

article in Famiglia Cristiana of 4 March 1979, which recalled

the facts. The following year, in issue 4 of the railway journal

Strade ferrate of November 1980, Nicola Raimo published

an article full of technical details and testimonies from the

survivor of the tragedy Luigi Ronga. In 1995 Renzo Pocaterra,

in the railway monthly Linea Treno, told the story of the

event, presenting Restaino's book (see next paragraph).

The first book on the Balvano massacre was "Un

treno un'epoca: storia del 8017" ("A train,

an era: history of 8017" published in 1994 by Mario Restaino

for Arti grafiche Vultur of Melfi (province of Potenza). The Rome

lawyer Gianluca Barneschi wrote two books on the massacre, "Balvano 1944. I segreti di un disastro

ferroviario ignorato" ("Balvano 1944. The

secrets of an ignored railway disaster") published in

2005 by Ugo Mursia Editore S.p.A., of Milan and "Balvano

1944. Indagine su un disastro rimosso" ("Balvano

1944. Investigation of a repressed disaster"), published

in 2014 by Libreria Editrice Goriziana of Gorizia. Alessandro

Perissinotto published "Treno

8017" ("Train 8017") for Sellerio

of Palermo in 2003, then republished by Gruppo Editoriale L'Espresso

S.p.A. of Rome, a detective novel that is closely linked to Balvano's

tragedy, the starting point of fictional events that take place

in the following years.

Final

thoughts

In many texts written

about Balvano massacre, the victims are described as black marketeers,

smugglers and trespassers, because they did not have a ticket.

In reality, the desperate situation in southern Italy, which had

just gone through the war, and with the front still a short distance

away, was such as to force many people to look for food in the

places where it was still available, i.e. in the countryside,

trying to barter it with every goods they could find by emptying

their homes: clothing, jewels, watches, and anything else that

might have value for those who had food to give away.

So it was something very different from the black market, which

according to De Mauro's dictionary of the Italian language consists

of the "illegal and clandestine purchase, at increased

prices, of monopoly, rationed and difficult-to-find products".

In the case of many passengers on train 8017, the goods acquired

were not intended to be sold at a higher price, but rather consumed,

so as not to die of hunger.

There may have also been black marketeers on board the death train,

but first of all, how can we distinguish them from the respectable

people described above? And why equate speculators and honest

people looking for food to take home?

The racist pressure came not only from the Anglo-Americans towards

the Italians, but also from other Italians towards their compatriots

from southern Italy. In 1956 Giulio Frisoli wrote: "the

convoy was packed with unauthorized passengers, mostly small black

marketers" (L'Europeo, no 12 (544), p, 55) and "the black marketers

did not give up their work, they rightly trusted on certain qualities

typical of southern Italy" (id., no 11 (543), p, 15). Yet the black market was also

commonly practiced in northern Italy!

As for the violations, it emerges from the testimonies that many

of the passengers on the freight trains were formally illegal,

but often had a ticket, regularly purchased on the ground or on

the train itself, emptied by the traveling staff in a regular

manner, with the issuing of "bills", but also in an

unclear way, even with payment in kind.

The distinction between regular traveler and illegal transgressor,

however, acquired its importance in the case of a request for

compensation from the victims' families: transgressors were not

entitled to anything, while regular travelers were. Death, however,

was the same for all of them.

Bibliography:

ARGENZIANO

Salvatore () Il Treno 8017 Una tragedia dimenticata Balvano, 3

marzo 1944 02 - Il Disastro dell’8017

BARNESCHI Gianluca (2005) Balvano 1944. I segreti di un disastro

ferroviario ignorato. Ugo Mursia Editore S.p.A., Milan, Italy.

BARNESCHI Gianluca (2014)

Balvano

1944. Indagine su un disastro rimosso. Libreria Editrice Goriziana,

Gorizia, Italy.

CAGGIANO Nestore (1957) Morirono 521 viaggiatori nella "galleria

delle Armi". Il Tempo, 25 May 1957, p. 10.

FRISOLI Giulio (1956) La più grande tragedia ferroviaria

di tutti i tempi. L'Europeo, n. 11 (543), p, 12-15; n.

12 (544) p. 52-55, n. 13 (545) p. 37-39.

ISTAT Istituto Nqzionale di Statistica (2022) Bilancio demografico

mensile e popolazione residente per sesso, anno 2022. link

MARTUCCI Corrado (1951) Nel tragico "merci" 8017 giacevano

quattrocento cadaveri. Oggi, n. 11, 15 March 1951,

p. 7-8.

MUSSA Cenzino (1979) E la morte scese sul treno. Famiglia Cristiana,

n. 9, 4 March 1979, 40-46.

PEPE Antonio Maria (2003) Balvano, un triste anniversario. La

Nuova Basilicata, 3 March 2003, p. 3.

PERISSINOTTO Alessandro (2003) Treno 8017. Gruppo Editoriale

L'Espresso S.p.A., Roma, Italy.

POCATERRA Renzo (1995) Balvano, l’inchiesta continua. Linea

Treno, May 1995, p. 30-31.

RAIMO Nicola (1980) Quella lunga notte del ’44. Strade

Ferrate, n. 4 November 1980, p. 33-38.

RESTAINO Mario (1994) Un treno un'epoca: storia del 8017. Arti

grafiche Vultur, Melfi, Potenza, Italy.

S.A. (1948) The 727th Railway Operating

Battalion in World War II. Simmons-Boardman Publishing Corporation,

New York, USA. link

S.A. (1951)

Italy Sued for Death on 427 on War Train. Chicago Tribune,

March 20th, 1951, link

S.A. (2014)

Treno 8017 in galleria, 70 anni fa 520 morti. Ansa.it Speciali,

6 January 2014 link

S G. DF.

- S. A. per www.vesuvioweb.com S. Argenziano. Balvano 1943. 02-Il

Disastro dell’8017 link

SAVINO Antonio

(2003) Un altro muro di gomma. La Nuova Basilicata, 3 March

2003, p. 3.

Websites consulted:

Digital

Library of the Italian Senate of the Republic (Avanti!)

link

Digital collection

of journals of the Biblioteca di Storia Moderna e Contemporanea

di RomaDigital collection of journals of the National Central

Library of Rome (Il Messaggero, Il Corriere della Sera, Il

Giornale d'Italia) link

Digital collection

of journals od the Modern and Contemporary Library of Rome (La

Domenica del Corriere, Oggi) link

YouTube -

Terry Allen - Galleria Dele Armi. link

Brigida GULLO

Balvano,

il Titanic ferroviario. Rai Storia. link

Wikipedia

- Disastro di Balvano https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Disastro_di_Balvano

Wikipedia

- Ferrovia Battipaglia-Potenza-Metaponto https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ferrovia_Battipaglia-Potenza-Metaponto

Treno di

luce http://www.antiarte.it/trenodiluce/galleria_delle_armi.htm

http://www.trenidicarta.it/treno8017/

page

created: March

1st, 2024 and last updated: March 10th, 2024

page

created: March

1st, 2024 and last updated: March 10th, 2024