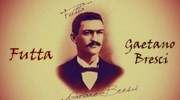

On 1900, Sunday July 29th at 10 PM Gaetano Bresci an Italian anarchist from Prato, near Florence, killed the king of Italy Umberto I firing him four shots while he was moving on an open carriage to the Villa Reale (Royal Villa) in Monza, near Milan, where he spent his summer vacation. At the time of his death Umberto was fifty-six years old and was a king for twenty-two years, from January 9th, 1878. Less than a year later they "killed himself" Gaetano Bresci in the penitentiary of the island of Santo Stefano.

Early

years

Gaetano Bresci was born in Coiano, a hamlet in the municipality

of Prato, on November 10th, 1869, a day before Umberto's

son, who became king at the death of his father with the name

of Vittorio Emanuele III.

According to Rivista Anarchica (1971)

Bresci was actually

born the same day as Vittorio Emanuele, but after the regicide

his birth date was changed, to avoid the coincidence. Petacco

supports the same thesis and writes that the original date can

still be found in the municipal registers of Prato. Actually,

the recent publication on the State Registry Offices website (link) of

the birth records written by the municipality of Prato, including

that of Bresci, (1st part and 2nd part), allows to verify that the registration

of the newborn Gaetano Bresci was performed on 13th

November by the midwife, who declared his birth on 10th

November, 1869 at 10 am.

Even the parish baptism register

reports November 10th as

birth date, and is

completed with two additions by canon A. Valaperti, written after

the regicide: one in Latin: "melius erat ei si natus non

fuisset homo ille" ("it would have been better

if that man wasn't born") and then "ad perpetuam

rei memoriam" ("for perpetual memory of the offender")

and one in Italian: "questo infame la sera del dì

29 luglio 1900 a Monza assassinò con 3 colpi di rivoltella

l'ottimo Re nostro Umberto d'Italia. Sia pace all'anima benedetta

di lui ed obbrobbrio sempiterno all'infame assassino"

("this infamous man on the evening of the day July 29th,

1900 in Monza murdered with 3 revolver shots our excellent King

Umberto of Italy. Be peace with the blessed soul of Him and everlasting

disgrace to the infamous murderer").

The native home of Gaetano lies in

Coiano in the locality "I Ciliani" in via delle Girandole,

58, currently named via del Cilianuzzo (according to Santin and

Riccomini the current name is via Baracca). Gaetano was the youngest

of four children of Maddalena

Godi, housewife aged fourty-four, and Gaspero (or Gaspare), farmer

aged fourty from Capezzana, owner of a small farm. The first-born

son Lorenzo was born on October 13th, 1856, he worked as a cobbler,

and was married with Stella Magri; the second-born son Angiolo,

born 1861, was a lieutenant in the 10th artillery regiment stationed

in Caserta; the third-born daughter Teresa was born June 18th,

1867, she was a housewife, and in 1890 she married the carpenter

Augusto Marocci from Castel San Pietro (Bologna).

Political

maturation

Gaetano started to work as a cobbler with his brother Lorenzo,

when he was a kid, then in 1880 his father made over the most

part of his arable land to Hans Kössler in order to get a

place as apprentice weaver for him at the "Fabbricone"

("the big factory") in Coiano di Prato, established

in 1888 by the German firm Kössler, Klinger, Meyer &

C. (Borsini). Eleven years old Gaetano worked

fourteen or fifteen hours a day, as he himself declared in the

trial. (Zucca) On Sundays he attended the municipal

school of arts and trades of textile and dyeing at Prato, becoming

a silk decorator, and as soon as fifteen years of age he was a

skilled worker. He worked as a weaver at Vannini company in Florence,

in Compiobbi and in Gello, with Cesare Zeloni firm. On February

26th, 1891 he lost his mother Maddalena. Gaetano

began to frequent the anarchist associations of Prato, and in

December 1892, at the age of 23, he joined the first strike, then

repressed by the military occupation of the factory, following

which Bresci resigned. The police then kept a file on him as "dangerous

anarchist", and he was sentenced on December 27th,

1892 by the magistrate of Prato for "contempt and refusal

to obey the public force" to a 20 liras fine and 15 days

of imprisonment, later remitted. He was found guilty of defending

vehemently, at 10 pm on October 2nd, 1892, a butcher boy who the

municipal police wanted to fine (Galzerano, pag. 115). According to other sources it was instead

a baker who was keeping the shop open after the closing time (Marzi). From the report drawn up by

the police it appears that Bresci told the policemen: "It

would be better if you went on your way, and leave this poor worker

alone. Weren't you workers? But sure, now you're not anymore!

Now you are the exploiters' servants. You are a bunch of spies

and vagabonds! " Bresci would have refused to declare

his personal information, but the following day he was reported

together with his comrades Augusto Nardini, Altavante Beccani

and Antonio Fiorelli (Zucca).

He was again detained, "for public safety measures",

in 1893 and 1895, and assigned for more than a year to confinement

in Lampedusa along with 52 other anarchists of Prato, in application

of the repressive laws issued by Francesco

Crispi. He was freed, together with his comrades, in May 1896,

thanks to an amnesty granted for the defeat of March 1th,

1896 in Adwa battle,

in the Ethiopian War.

On December 22nd, 1895 Gaetano lost his father

Gaspero, who was aged sixty-five (link

with the death records of Prato municipality). In the following

years he found difficult to be hired for his criminal record ,

and he frequently changed employment, although one of his employers

testified at the trial: "I must honestly allow that I

had few workers like him". After having sought in vain

a job in Prato, he moved to Ponte all'Ania,

a hamlet of Barga in the upper part of Lucca province, where in

1896 he was hired by "Michele Tisi & C." textile

factory.

In Ponte all'Ania it seems that he often went on the banks of

Ania creek to shoot the pebbles, showing

he had excellent aim. In summer 1897 he had a son from (Maria

or maybe Assunta Righi), a coworker, and at the beginning of autumn

he returned to Coiano to borrow thirty liras from his brother,

to contribute to the expenses for the baby (the so-called "baliatico").

Then he returned to Ponte all'Ania for a few weeks; at the end

of October he resigned from Tisi company, then came back again

to Coiano, where he announced that he would go to America.

Despite being self-taught, Bresci always showed an excellent cultural

level and a multiplicity of interests, which went beyond politics.

The Santo Stefano prison doctor, Francesco Russolillo, told that

his eyes "concealed burning flames and abysses"

and that Bresci "had a culture and a soul that, hadn’t

they been turned to evil by a work of moral destruction, would

have made of him the best of intelligent workers." (Galzerano, pag.

803)

In the

United States

Bresci left Genoa

with the steamer "Colombo" on January 18th,

1897, landing on January 29th in New York where he was hosted

by his comrade Gino Magnolfi. As soon as he arrived he found a

job in Pennsylvania, and a year later at Givernaud & Co. and

Schwarzenbeck silk factories in West Hoboken (currently Union

City), in New Jersey, where he stayed for about three years. Then

he moved to Hamil and Booth Co. silk factory in Paterson, also

in New Jersey, about 20 km from West Hoboken and 21 miles (34

km) from New York, and then to Emelburg. He stayed in Paterson

the entire week, dwelling at Bartholdi's Hotel and having dinner

at Both boarding house, on 345, Straight Street, also named Italians’

Road, and returned on Saturdays at West Hoboken, where he had

kept his home, on 263, Clinton Avenue, and where in August 1898

his partner Sophie Knieland came

to live with him. She was born in New York in 1865 and she had

Irish origin and they met in April in Weehawken park. According

to a deposition issued by Sophie after the regicide, she and Gaetano

had married before a justice of the peace. Gaetano and Sophie

had two daughters, the eldest, born on January 8th,

1899, was called Maddalena (Madeline), like her paternal grandmother,

and the younger, who was born after the attack, on September 28th,

1900, was named Muriel, also known as Gaetanina.

Paterson was a city of immigrants, with a strong Italian presence,

and was an important anarchist center in the USA, where Bresci

found many fight comrades he met in Italy. According to The New

York Times of December 18th, 1898, two thousand five hundred

out of ten thousand Italians residing in Paterson, declared themselves

anarchists and three thousand five hundred purchased regularly

the anarchist journal in Italian language "La

Questione Sociale" (Mazzone).

One week after his arrival, Bresci enrolled in the Society for

the Right to Existence; a month later he bought ten one-dollar

shares of "Era nuova" publishing company. Bresci

collaborated with "La Questione Sociale", for

a period directed by Errico Malatesta,

who arrived in Paterson in August 1899, coming from London, via

Tunisia and Malta, reached after escaping from his confinement

in Lampedusa, on the night between April 29th

and 30th, 1899.

Bresci took regularly part in meetings, even if he did not talk

frequently, and when he did so he spoke calmly and without raising

his voice. He often began with the foreword "a little

observation", which became a sort of nickname with which

he was called.

In Paterson Malatesta, a supporter of the collectivist tendency,

had arguments with the individualist anarchist Giuseppe

Ciancabilla from Rome, director of the other anarchist newspaper

of the town, "L'Aurora", who until 1897 was a

socialist, collaborator of Socialist Party’s newspaper "Avanti!".

On August 30th, 1899 in Tivola and Zucca's Saloon,

on Central Avenue, West-Hoboken the two anarchists clashed in

a virulent quarrel, during which Bresci would have saved Malatesta's

life, tearing the revolver from the anarchist barber Domenico

Passigli’s (according to others "Pazzaglia") hands,

who had attacked Malatesta, wounding him in a leg.(see the

news on "Avanti!"

of 18 September). The same Bresci, during the regicide's trial,

testified that he wasn’t there during the argument (Galzerano, pag.

106), while in another interrogatory

confirmed that he had disarmed the barber, while Ciancabilla wasn’t

there (Galzerano,

pag. 118).

The newspaper "Gazzetta

di Torino" of August 2nd, 1900 presented the event as

no less than "an American revolver duel". In

the ideological controversy between the two Bresci was closer

to the individualist positions of Ciancabilla, whose newspaper

"L’Aurora" applauded the regicide of Monza,

while Malatesta, in an article entitled "Cause ed effetti"

didn’t subscribe to Bresci’s deed, though identifying

its causes in social injustice.

Preparation

of the attack

In February 1900 Bresci

disclosed to Sophie his impending trip to Italy, and on May 7th,

he resigned from his job in the factory and on May 10th

he asked two comrades to buy him a ticket. He embarked on May

17th, 1900 on the French steamer "La Gascogne" of the Compagnie

Générale Transatlantique, traveling in third class

and taking advantage of the 50% discount for the visitors of the

Exposition Universelle

in Paris. At the end of May Bresci disembarked at Le Havre and

then went to Paris, where he visited the Exposition. Later he

made a stop in Genoa, and on June 4th he reached Prato, where the police

commissioner rejected to grant him a firearms license. From 20th

June to 8th July he was in Castel San Pietro

(province of Bologna), where his sister Teresa lived with her

husband, who was also Bresci's workmate at the Fabbricone. In

Castel San Pietro he stayed at the Osteria della Palazzina, managed,

together with her husband, by Stella Magri's sister, wife of her

brother Lorenzo. On July 8th he went to Bologna to attend

the commemoration of Giuseppe Garibaldi, by the monument

to the hero, which had been inaugurated

less than one month before, then returned to Castel San Pietro,

on July 19th and on July 20th

he was in Bologna, then in Parma, Piacenza and on July 27th,

he arrived in Monza, where Umberto stayed since the Saturday of

the previous week, July 21st. Bresci arrived in the morning

in Monza railway station and

found an accommodation not far from there, in a boarding house

in via Cairoli 14.

Some student deem that Bresci developed the idea of attacking

the life of Umberto as he disembarked in Italy, but the prevailing

thesis is that he had left the USA specially to carry out "the

wicked plan of the execrable regicide", as can be read

in the decree of commitment for trial. In Prato the anarchist

practiced at the National

Firing Range of Galceti. There are testimonies of how Bresci

was proud of his aim, and how he frequently gave practical demonstrations

of it, using bottles as a target, which he managed to break by

passing the bullet from their neck.

The attack

On the evening of

July 29th, Bresci went to the training

field of the Gymnastic Club "Forti e liberi",

in via Matteo da Campione, very close to the Villa Reale, where

the king had to reward the athletes at the end of a gymnastics

exhibition. The anarchist at 9:30 pm saw the king arrive on a

Daumont carriage pulled by two pairs

of horses. but he did not attempt the attack and just identified

Umberto, to prevent confusing him later with the other passengers

of the carriage. The anarchist was elegantly dressed, with a straight

collar, a black necktie, a pocket watch with chain and a ring

on his finger. He had the Hamilton & Richardson, "Massachussets"

of 1896 five shot revolver with

him, which he had bought for 7 dollars in Paterson on 27th

February, on each bullet he had made with scissors several incisions,

as they told him the American bandit Jesse

James used to do, in order to increase their dangerousness,

making the penetration easier in case the king had worn an armor,

and making easier the wounds to infect.

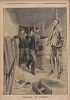

At 10:30 pm, after the prizes awarding ceremony, the king went

back into the carriage and was about to leave the gymnasium field,

heading for the Villa Reale, a few hundred meters away. Lieutenant

General Emilio Ponzio Vaglia, minister

of the Royal Household, and Lieutenant General Felice

Avogadro di Quinto, first aide-de-camp were with Umberto.

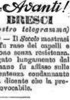

In the map published by the socialist

newspaper "Avanti!" the place of the attack is

shown, and a cross marks the position of the carriage. The king

was standing inside the open carriage and about to sit down, when

Bresci fired the four shots being only a few steps away.

Umberto was reached by

the first shot in the back side of his neck, then he turned instinctively,

and was hit by two more shots in the chest, in the cardiac region,

while the fourth bullet was found, without blood traces, on the

bottom of the carriage, and therefore it didn't hit the target,

maybe because it was deflected by a punch that the Marshal of

the Carabinieri Giuseppe Braggi gave Bresci's arm. Umberto collapsed into the carriage and ordered

the coachman: "Go ahead, Go ahead!" and, asked

how he felt, replied: "I don't think it's anything serious".

He was taken to the Villa and laid down on his own bed,

where after fifteen minutes after the attack he died.

The three shots out of four that hit the target testify to the

good aim of Bresci, while the fifth cartridge in the revolver

was not fired, and was found in the cylinder, along with the four

casings of the bullets which were fired.

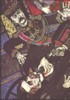

The artist Flavio Costantini (1926-2013) depicted the regicide in several

works (1 , 2

and 3). The weekly journal "La

Domenica del Corriere" published a picture

of Umberto which indicated as a possible last photo taken

to the king.

Why the

attack was made?

The motive of the

attack was the revenge for the massacres of workers, ordered to

repress uprisings of protest, like those in Conselice (province

of Ravenna) in 1890, in Sicily and in Lunigiana in 1894 and in

Milan in 1898, where the Army

fired on the protesting crowd, assassinating hundred of persons

(the exact number has never been assessed). The Milan rising arose

from the ill-famed "grist-tax" which provoked a huge

increase of bread and flour prices, whence followed the assault

to the bakeries and the hardest repression, carried on even by

means of guns. In addition to the slaughter of workers, also the

massacre of 9,000 Italian soldiers in the catastrophic Ethiopian

War of 1896 planted the seeds for the regicide.

The anarchicot Amilcare Cipriani in

the booklet "Bresci e Savoia"

of September 1900 wrote: "from the immense crowd of victims

of misery and massacres of Lunigiana, Sicily and Lombardy an avenger

arose, Bresci" (Galzerano, 2001, pag.41). It's clear that the support given by Milan

bourgeoisie to the repressor troops, with the slogan: "Tirez

fort, visez juste" ("shoot hard, aim right")

had been received by Gaetano Bresci, who declared at the trial:

"after the state of siege in Sicily and Milan, illegally

established by royal decree, I decided to kill the king to avenge

the pale victims".

The same Umberto I, to whom many people attribute the political

responsibility of the massacre, awarded with the Grand Officer

Cross of Military Order of Savoy and with the appointment on June

16th, 1898 as Senator of the Kingdom the Piedmontese

general Fiorenzo Bava Beccaris, who had

ordered the massacre, as Royal Special

Commissioner with full powers, congratulating him for

defending the civilization. The journalist Paolo

Valera, a witness of the massacre, wrote in 1899: "In

the phraseology of the general you always find something of the

master who talks to his servant and something of the imbecile

who has taken from the military school nothing more than the brutality

of his trade". During the trial, Bresci recalled the

massacres committed and the fact of having seen "the authors

of the May massacres being rewarded instead of hanging them"

as the cause of the regicide. The anarchist Armando

Borghi remembers how after 1898 in the revolutionary circles,

the killing of Umberto I was considered "a useful first

step towards a republican revolution".

The intolerance of Umberto and above all of his wife, the Queen

Margherita for the protests of the people, shared by many of the

military top ranks and by the industrialists, brought to elaborate

a project of institutional coup d'etat, which foresaw the dissolution

of the Parliament, seen as inactive and infiltrated by the socialists,

transferring the power to the king and to the most reactionary

politicians.

The authoritarian turn of the end of the century was completed

by a law which reduced the electoral body by 847,000 electors,

lowering the voters' percentage on the total population of Italy

from 9.8% to 6.9% (Feldbauer).

Bresci's attack was not the first assassination attempt against

Umberto I: previously Giovanni Passannante,

from Salvia di Lucania (province of Potenza), on November 17th,

1878 in Naples and Pietro Acciarito

from Artena (province of Rome), on April 22nd,

1897 in Rome,

on the Appian way, as the king was heading to Capannelle

racecourse tried in vain to stab the king. For Acciarito the trigger

of the attack was the indignation for the fact that the king had

offered a 24 thousand liras prize to the winning horse, while

many Italians, including Acciarito, were in serious financial

straits (Centini).

Giuseppe Ciancabilla in Paterson's "l'Aurora"

wrote "The mistakes made by Passannante and Acciarito

taught us that today that a repeating handgun is more reliable

than a dagger!", While the same Umberto I, after the

two knife attacks, had foreseen that when the attackers will have

left the dagger aside and grab the gun he would be doomed. (Felisatti)

The newspaper Il Messaggero of 18 May 1890 reports a deed

demonstrating that Umberto was aware of the danger of a good gun

shooter: when he visited a shooting competition he saw that a

famous fencing master had obtained an excellent score in the shooting

gallery, and he shook his hand, congratulating him and commenting:

"much better than a sword!".

Umberto

Umberto, who ascended

to the throne on January 9th, 1878, was known, according to

the iconography favorable to him, as "the good king",

but the massacres he ordered or endorsed earned him the popular

name of "grapeshot gun king".

According to the patriot and minister Silvio

Spaventa King Umberto "is unfortunately ignorant:

that is to say that he does not have the necessary and adequate

culture for his time and degree". Umberto himself said

to his son: "remember that it's enough for a king to know

how to draw his own signature, read the newspaper and ride a horse"

(Galzerano,

2001, pag. 147).

According to his aide-de-camp, lieutenant-colonel Paolo Paolucci

delle Roncole, the king had no interest or cultural curiosity

and no tendency for arts, he didn't read any book and even writing

was painful and tiring to him (Silipo).

The anti-fascist historian Gaetano

Salvemini (1873-1957) in “Terrorismo e attentati individuali”

of 1947 wrote: "Umberto was a tyrant in the classic sense

of the word, supporting the strangulation of liberties [...] Bresci's

memory is surrounded by a halo of sympathy and gratitude in the

conscience of many Italians [...] the great majority of the country

found that Umberto had not stolen that revolver ball".(Sacchetti).

Francesco Crispi defined Umberto “a chump who let himself

be guided by false scruples of constitutionalism”, the

mayor of Rome Alessandro Guiccioli accused him of lack of will

and of the “clear insightfulness of the high and noble

mission that [he] would be entitled to”, while the President

of the Senate Domenico Farini judged him to be scarcely frank,

fickle, often ignoring anything, nor reading the newspapers. Once

he had gone to talk about a serious government crisis, he realized

that Umberto had fallen asleep, moreover, he didn't think anything

else than hunting or women, leaving himself vulnerable to a thousand

gossip. (Felisatti)

Umberto was known

for his hectic sexual activity, in addition to his wife he had

an official mistress, the duchess

Litta, née Eugenia Attendolo Bolognini, who was also

lover of his son Vittorio Emanuele and of Napoleon III,and who

was involved in the financial scandal of the Banca Romana, and

acquitted like all the other powerful persons under investigation

(Lisanti). Umberto anyway also frequented

Rosa Vercellana "la bela Rosin"

("the beautiful Rosie"), who had became official

lover of his father at the age of 16. Umberto needed a continuous

turnover of women, chosen from photographs, received at the palace

and dismissed with an envelope containing money, which calls to

mind more recent Italian rulers, as well as the passion for underage

girls, for example the fourteen-year-old Cesarina Galdi, a Count's

daughter, who he had made pregnant, as she herself reported after

the regicide.

(Galzerano,

2001, pag. 147-155)

After

the attack

Bresci let himself

to be arrested soon afterwards

the regicide, whitout offering resistance, and declared: "I

didn't kill Umberto. I killed the king. I killed a principle."

At least eight people competed for the "credit"

of having stopped Bresci; immediately after that some of the bystanders

tried to lynch him, and the police avoided it happened. The anarchist

always showed a calm demeanor, and three days after the attack

a newspaper informed: "he always eats cynically".

(Galzerano,

2001) Right after

the attack the authorities established a kind of cordon sanitaire

around Monza and the news about the regicide spread with difficulty.

The first journalistic reports

displayed that the regicide was a certain Angelo Bressi, then

they corrected themselves and

provided more details.

The criminologist Cesare Lombroso (1835-1909),

close to socialist ideas, in a text of 1894 had defined Passannante

and Acciarito as insane and degenerate, while he classified Bresci

as a "criminaloid", with mediocre intelligence,

who had suffered the impoverishment of his family of origin. He

was driven to crime by fanaticism, though not being part of a

plot, incompatible with the indiscipline and the amorphism that

Lombroso attributed to the anarchists (Galzerano, 2001, pag 838). Moreover Lombroso, speaking

of Bresci, said that there were no signs of pathology or criminal

traits (according to the pseudoscience of the time), claiming

that for the regicide “the urgent cause lies in the very

difficult political conditions of our country” blaming

"the maximum guilt of the ruling classes [which is] not

to heal the evils that spoil us but to inexorably strike those

who reveal them. A strange remedy indeed, which would be enough

by itself to show how deep have we descended.” (Zucca)

Lev

Tol'stoj so commented the regicide: "Those ones, you

always see them in their military uniform bearing at their side

the instrument of the murder, the sabre. Murder is a job for them.

But if only one of them is murdered, then you'll hear them complain

and be indignant".

The French socialist newspaper "L'Aurore", the

same that on January 13th, 1898 had hosted the "J'accuse" by Émile

Zola, that reopened the Dreyfus affair, published on August

1st a commentary

by Albert Goullé that ended with "When a head of

state orders the death of twenty, fifty, a hundred men of the

people, the murdered are blamed as criminals. When a man of the

people becomes an avenger of the murdered, he is the abominable

murderer."

The anarchist activist Luigi Galleani defned Bresci as “The

sparkling archangel of popular revenge and social justice”,

while Armando Borghi in “Errico Malatesta” (Milan,

1947) wrote “Bresci came to us from abroad armed with

three requirements: an iron will, a precision handgun and excellent

shooting quality" (Rosada).

The Communist leader Palmiro Togliatti,

in his article "Due date" ("Two Dates")

published on "Il comunista" of August 17th,

1922 wrote: "The violent death of Umberto was the surfacing,

in a tragic and heightened form, of a deep conflict, of a contrast

of real forces […] that is still up to the history to solve.

In the firm hand and in the trustworthy eye of the individualist

anarchist almost symbolically the will and the strength of the

masses took their shape, angrily raised to protest against the

power of the Italian State oppressor, starver, shooter and cop"

(Affortunati,

pag. 81).

Giuseppe Galzerano in his very complete work on Gaetano Bresci

(2001), shows a review of comments published

in various countries, after the attack, showing that several Italian

who carried out attacks against heads of state were considered

as heroes. The examples are Felice

Orsini who had carried out an attack against Napoleon III,

emperor of France, Guglielmo Oberdan,

who had attempted to kill the Austro-Hungarian emperor Franz Joseph,

Agesilao Milano, who tried to

assassinate the King of the Two Sicilies Ferdinand II, Antonio

Carra, who had stabbed to death the Duke Charles

III of Parma. Amilcare Cipriani, in the booklet mentioned

above, commented: "I do not understand the reason why

the same act, according to the person who commits it, or to whom

it is aimed, is considered an act of heroism or a murder." (quoted by Galzerano,

2001, pag. 52)

Among the authorities

who presented their condolences for the death of Umberto was US

President William McKinley, who about

a year later, on September 14th, 1901, died as a result of the

revolver shots that eight days earlier the American anarchist

of Polish origin Leon Czolgosz had

fired to him in Buffalo, inspired by the gesture of Gaetano Bresci,

so much so that a newspaper clipping on Monza attack was found

on him.

Bresci was taken to Monza jail where he was interrogated and tortured,

as reported by the anarchists, but also by the Socialist MP Filippo Turati, on "Critica

sociale", and as can be guessed by various details,

such as the blood stains left on the carriage that transferred

him from Monza to Milan and as the way he moved limping. During

the trial one of the attending journalists wrote "He still

bears the markings of beatings on his face" (Petacco). The anarchist always maintained

a calm demeanor, apart from the protests for the obligation to

wear a straitjacket, motivated by the need to prevent him from

committing suicide, which appears as an early building of an alibi,

for the purpose of supporting the future sham suicide of Santo

Stefano.

Gaetano's

family after the attack

In 2020 Andrea Sceresini published on "La Repubblica"

unpublished news about what happened to Gaetano Bresci's wife

and daughters after the attack in Monza. Sophie Knieland changed

her surname into Niel (Mazzone) and,

after Gaetano's death, she moved to Cliffside Park, New Jersey,

whose mayor in September 1901 ordered her to leave "to

prevent any problems". Sophie remarried with trade unionist

of German origin Joseph Mang and went to live in Newark suburbs,

near New York. In 1912 Sophie and Mang separated and she moved

to Chicago, where Muriel was entrusted to the custody of a group

of anarchists, while Sophie and Madeline moved to Glacier Park

in Montana, where the mother worked as a cook at a cafeteria.

In 1913 the family gathered in Seattle, and after a year moved

to California, where Sophie worked as a cook and her daughters

went to work as cleaning ladies by families, then moved in San

Francisco on Monterey Boulevard. Mother and daughters opened a

food kiosk in the port area, at first they had problems with the

local organized crime, solved thanks to the help of the dockers,

later Sophie opened a beauty salon and the daughters founded a

female musical group, the "Lorelei Syncopaters"

(see picture, Madeline and Muriel are

third and fourth from left). Sophie died in San Francisco in 1932

at the age of 67. Madeline married and died in San Francisco in

1974. Muriel married, had three daughters and moved to Fresno,

in California, where she died in January 1981, and was buried

in the local cemetery with the name of her husband, Mitchell.

The "conspiracy"

During the interrogatories

the Carabinieri police tried to compel Bresci to confess he had

accessories, what the anarchist never allowed, explaining instead

to his jailers the reasons for his deed. Bresci gave answers of

an "unrivaled sharpness", irritating the Colonel

of the Carabinieri for "the unfortunately convincing way

with which he expressed himself." (Galzerano)

After the attack news

and imaginary testimonies circulated on the world press about

the appearance of Bresci before the attack in the most disparate

countries, from Budapest to Barcelona, from Bratislava to Geneva,

from London to Brussels, from Vienna to Fiume and no less than

Buenos Aires.

The famous Italian-American detective Joe

Petrosino had also investigated in the libertarian circles

of Paterson to discover accessories and instigators of the Monza

attack, concluding that the regicide was the result of a plot

hatched by a group of Paterson anarchists affiliated with the

"Black Hand" (which at the time still had libertarian

implications) and that Bresci had been designated by drawing lots

with the raffle numbers. (Toscano) During

the investigation on McKinley murder, Petrosino interrogated and

heavily mistreated Sophie Knieland, Bresci's partner. (Toscano)

During the investigations,

in Italy and in the USA, a plethora of people came to light who

witnessed, after the attack, they were informed in advance, by

numerous and heterogeneous accomplices of Bresci, who often proved

to be non-existent on public records. The Socialist newspaper

"Avanti!" of August 26th,

1900 commented: "The accessories of the regicide are now

more numerous than Xerxes' soldiers: red and black, yellow and

blue, have prepared the crime." (Galzerano, 2001, pag. 341)

The upper echelons

of State Security, and in particular the Minister of the Interior

Giovanni Giolitti, followed with great

conviction the lead of a plot managed by the former queen of the

Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, Maria Sophie

of Bavaria, in exile at the time at Villa Hamilton in Neuilly-sur-Seine,

near Paris, whose parlor, in addition to aristocrats and intellectuals,

hosted anarchists and socialist and republican revolutionaries,

favorably viewed as anti-Savoy. For these acquaintances Maria

Sofia was called by Marcel Proust "queen of the anarchists",

although she was the sister of Elisabeth of

Bavaria, called "Sissi", empress of Austria who

was killed in Geneva in 1898 at the age of 61 by the Italian anarchist

Luigi Lucheni. In addition to suspecting

that Maria Sofia had funded and protected Bresci and other alleged

conspirators, the Italian secret services, infiltrated among the

Italian anarchists in exile, were convinced that a plan was in

place to free Gaetano Bresci from his jail, and later from the

penitentiary.

A further lawsuit for the murder of Umberto, dedicated to the

alleged accomplices of Bresci, despite the wide number of people

under investigation, even in a brutal way, failed to go beyond

the investigation stage, for the absolute inconsistency of the

evidence collected.

Years later, Pietro Acciarito, the failed regicide of 1897, when

asked if Bresci had been instigated by someone, replied: "Whatever

society cannot take a man and tell him to kill. I say that

Bresci acted alone, if he ever had an encouragement, it was from

misery."

(Galzerano,

2001, pag. 345)

For many years, however,

the anarchist Luigi Granotti, from

Sagliano Micca (province of Biella), known as "il biondino"

(although he was not blond) was pursued as an accomplice of Bresci.

Granotti had come to Italy from Paterson two weeks after Bresci,

and was with him in the days of the regicide at Monza, which he

would have reached by train together with Bresci. Granotti would

have searched an accomodation with Breaci in the same boarding

house, and as he hadn't find it, he would have stayed at the locanda del Mercato, laying in the

same area

Granotti fleed from Italy a few days later, crossing the Alps

to Gressoney, and passing through Switzerland. Despite the sentence

to life imprisonment in absentia received on November 25th,

1901 it is not at all certain that Granotti took part in the regicide

or that he was aware of it in advance. Luigi Granotti was chased

for decades, with numerous false sightings all over the world,

from Shanghai to Buenos Aires, from London to San Francisco, from

Chicago to Singapore, and in any case he never returned to Italy

and died in New York in 1949. (link)

The reaction

The regicide triggered

the response of the most reactionary sectors of the country. The

city of Prato, birthplace of Bresci and Monza, the unaware scene

of the regicide, were hit by a sort of damnatio memoriae,

so much so that the Royal Villa of Monza, habitual venue of royal

vacations, was practically abandoned.

On the training field of the sporting society "Forti e

liberi", in the exact point of the regicide, a memorial

chapel was built in the form of a stele, called "Cappella

reale espiatoria" ("Royal Expiatory Chapel")

inaugurated in 1910, where a memorial

stone can be seen in the crypt, placed on the exact spot where

Bresci killed Umberto. The headquarters and the training field

of the sporting society "Forti e liberi" were

transferred and still lie in via Cesare

Battisti, few meters away from the original place.

The revenge against Bresci by the reactionaries and the establishment

also involved his family: his brother Lorenzo, a shoemaker, was

persecuted and imprisoned until he took his own life three years

later. The other brother, Angiolino, who had chosen the military

career and was an artillery lieutenant, was forced to change surname,

acquiring that of his mother, not to lose his job. Many other

Italians named Bresci preferred to change surname to avoid reprisals

and assaults. His brother-in-law, Augusto Marocci, worker at the

Fabbricone, and the Union organizer Giulio Braga, together with

other anarchists from Prato, including Luigi and Carlo Masselli,

were also arrested, when surprised to tear off the insignia of

national mourning.

The Milan newspaper Corriere della Sera of August 9th,

1900, in a correspondence from Paris, even blamed primary education

as a factor of incitement to regicide, since it allowed the workers

to read, and then to refer to subversive newspapers. The evidence

would have been the failed attack

to the Shah of Persia Muzaffar al

Dîn in Paris, on August 1st, three days after Monza regicide,

whose perpetrator, the anarchist François

Salson, would have been instigated by reading about the deed

of Bresci. (Galzerano,

2001, pag. 217) The

liberal philosopher Benedetto Croce

(1866-1952) mentioned Bresci as "an anarchist

who came from America" without even mentioning his name. (Petacco)

The reactionaries

also attacked Republicans and Socialists and their clubs, while

the forces of law and order not only avoid defending the assaulted

people, but instead arrested them and beat

them in turn.

The socialist Alfredo Angiolini (1900) wrote:

"There was therefore no reason to inveigh against the

socialists, yet the reactionary newspapers began to speak of conspiracies,

accused the socialists as instigators and moral responsibles of

the murder, called for new provisions, new exceptional measures

against all subversives, they made pressure on the ministry to

re-enact those liberticidal methods that had characterized the

Pelloux government, inciting the rascals and scum of the society

against the socialist newspapers, against the democratic society."

For over a year hundreds of trials for justification of a crime

were held, for facts that were totally negligible, if not ridiculous,

but which often ended with convictions for the defendants, giving

moreover the feeling that the Italian people as a whole were far

from blaming the regicide and instead Bresci enjoyed a great sympathy

and solidarity, especially among the lower classes.

The Catholic Church distinguished itself for an extreme coldness

towards the mourning of the royal family and of Italy, with whom

there were no diplomatic relations after the conquest of Rome,

with the breach of Porta Pia

on September 20th, 1870 (see my webpage).

The Pope Leo XIII, who was ninety

years old, refused to allow any religious rites in memory of Umberto.

The Vatican newspaper L'Osservatore Romano explained with an icy

laconicity the hostile attitude of the Catholic Church towards

the House of Savoy. Furthermore, several priests were sentenced

for justification of the regicide.

The trial

The case was prepared

for the trial in just one month, on August 17th

the Prosecution Section issued the indictment verdict. By decision

of President Luigi Gatti, the trial lasted only one day, from

9:00 AM to 6:00 PM of August 29th 1900, in the Court of Assizes

of Milan, in the palace of the Captain of Justice, in Piazza Beccaria,

heavily guarded by troops. The court refused the request of the

defense to have a postponement of the trial to more serene times.

Bresci asked to be defended by Filippo Turati, who, after a talk

with him on August 20th, the next day informed him of

his refusal, even because he hadn't been practicing for ten years.

Turati described the prisoner as pleasant, without abnormal traits,

but with "a detached and detemined person, almost glacial,

so that he makes his thought impenetrable", but who cared

about not looking like an ordinary criminal. The socialist leader,

however, judged him to have a very poor intelligence. (Galzerano, 2001,

pag. 235)

Turati's ideas about

the Monza regicide are clearly expressed in an article attributed

to him, "La successione", published in "Critica

Sociale" of August 1st, 1900: "one of those

lunatics, who at all times poured out their impulsive irritation,

and that in modern times - due to an ever more attenuating remnant

of the psychology generated by bourgeois revolutions - sometimes

still mislead themselves that they could modify something essential

in the political device, killing those who embody its most superficial

and decorative part" (Galzerano, 2001, pag. 445)

Turati recommended to Bresci to entrust his defence to the lawyer

Francesco Saverio Merlino, from Naples,

who in his youth had been an anarchist, formerly a political agitator

in the United States with the task to organize the Italian workers,

also in Paterson in november 1892, even if at the time of the

trial his sympathies were for the Revolutionary Socialists, although

he wasn't involved in political life. In 1895 Merlino, while he

was detained, was nminated for the political election in Prato

electoral constituency, supported by anarchists and socialists

(Affortunati,

pag. 59). Merlino

was appointed the day before the trial, and asked in vain for

a postponement to study the huge amount of papers, and to summon

witness for the defence residing in the US, also to ascertain

the possible existence of a plot born in Paterson of which Bresci

would have been the actual executor. Merlino was flanked by lawyer

Mario Martelli, chairman of the

Milan Bar Association, who initially was the court-appointed lawyer.

The reporters of the bourgeois newspapers went wild with negative

descriptions of Bresci, calling him "unpleasant",

"wicked", "discouraged and overcome",

"irritable and asymmetric", "repulsive",

"viper", "wild beast", "degenerate",

"reptile", "abject" and "pervert".

Physically he was "rather ugly", according to

others "very ugly", with "sunken eyes",

"surly look", "evil stare",

"big nose", "short and protruding

(?!) chin", and even "long nails". Moreover

he appeared "bony but not mighty", "skinny",

showing "very marked facial features", characterized

by "deep pallor of his face", "very weak

and trembling voice", "lacking any physical and

mental energy", not to conceal the fact that he "displays

ferocity and induces repugnance", and that "the

repugnance he provokes becomes aversion." (Galzerano, 2001,

pp. 270-275)

The newspaper Il

Correre della Sera of August 31st, 1900 even got angry with Bresci's

daughter, Maddalena, "frail and sickly, at eighteen months

had not yet got her front tooth." (Galzerano, 2001, pag. 322)

Also during the trial

the public prosecutor, in the person of the locum tenens Attorney

General at the Court of Appeal of Milan Nicola

Ricciuti, tried to substantiate the thesis of an anarchsts'

conspiracy to kill Umberto, which in his opinion was proved by

the fact that the defendant came from Paterson, the location of

a big anarchist colony. Bresci however always maintained he acted

alone and on his own initiative.

Mr. Merlino arrived from Rome without being able to sleep because

he had to study on the train the documents which were available,

and was followed by plainclothes policemen. During the hearing

he was interrupted several times by the court, by the public prosecutor

and by the public, that according Naples newspaper "Il

Mattino" was made of "journalists, plainclothed

cops and carabinieri", and tried to make them all reflect

on the fact that the violence of individuals was fueled rather

than stifled by the violence and repression of the state, and

on the utility of doing justice, rather than doing revenge, in

order not to generate further acts of violent rebellion, such

as the regicide.

Mr. Martelli in his brief defensive closing statement argued instead

that Bresci, although not crazy, was obsessed with the wrong identification

of the king with the state, and also asked him to do justice and

not revenge.

Bresci was sentenced for the crime of regicide "to the

life imprisonment, of which the first seven years in continuous

seclusion in cell, to the perpetual disqualification from holding

public office, to the legal deprivation, to the deprivation of

the testamentary capacity, considering null and void a will which

by chance he made before the sentence" (the death penalty

had been abolished in Italy in 1889 by Zanardelli's Penal Code).

The article 117 of the same code established: "Any person

who commits a deed targeted against life, integrity or

freedom of the sacred person of the King is punished with life

imprisonment" while the article 12 of the same Code established

that "life imprisonment is perpetual. It is served

in a special establishment, where the convict remains for the

first seven years in continuous cellular confinement, with the

obligation to work". It seems that his partner Sophie,

when got the news of the condemnation, forwarded a petition to

the queen mother, even if this circumstance was denied by the

anarchist environments of Paterson.

Bresci refused to lodge an appeal against the judgment to the

Court of Appeal; he was visited in jail by lawyer Mr. Caberlotto,

a collaborator of Mr. Martelli, and declared that he was only

appealing to the forthcoming Revolution. The judgment of conviction

was affixed on September 8th,

on the corners of Milan.

Santo

Stefano

Bresci's detention

and transfer procedures were always kept hidden for fear that

his anarchist comrades would try to free him. The convict was

first secluded in Milan's jail of San Vittore, then he was boarded

in La Spezia on November 30th, 1900. and on January 23rd,

1901, at 7 o'clock he was disembarked by the Italian Royal Navy

paddle wheel aviso ship "Messaggero"on

Santo Stefano island, in the Pontine Islands archipelago (see

my webpage), and at 12 he was

taken on responsibility of the register of the penitentiary

on the island.

During the sea transfer to Santo Stefano, the crew had order of

not speaking with Bresci, but it seems that a sailor, Salvatore

Crucullà, during the transfer by rowing boat from the "Messaggero"

to the island, asked the anarchist why had he killed the king.

Bresci would have replied: "I did it also for you",

triggering the laughter of the crew, who did not understand the

meaning of the sentence.

The arrival and departure dates are inconsistent with the relatively

short distance between La Spezia and Santo Stefano, and this could

be explained by a halfway detention, mentioned at the time by

the newspapers, in Portoferraio penitentiary,

on the Elba island. Bresci was detained in one of the twenty cells

of the isolation section called "La Rissa", three meters

below sea level, where Bresci, under a window, would have written

the sentence: "the grave of the buried alive."

The time spent in Portoferraio would have been the delay needed

to set up the cell allocated to Bresci in Santo Stefano (Zucca), but according to Petacco the

transfer was due to the solidarity of the other prisoners with

Bresci, also due to the continuous detention in chains, which

wasn't allowed anymore by law.

According to a report published by Naples newspaper "Il

Mattino", written by Cavalier G. Di Properzio, who visited

Santo Stefano two days after the official death of Bresci, the

prisoner in disguise left Milan to reach La Spezia, with a direct

train on the evening of January 21st, 1901, escorted by the Director

General of Prisons Alessandro Doria and by five Carabinieri. From

La Spezia station, always in disguise, and completely shaved,

he would have been taken with a public carriage to the Arsenal,

where he would have boarded the "Messaggero"

towards Santo Stefano, arriving almost two days after.

In Santo Stefano a special cell

was purposely modified for Bresci, the General Prison Department

sent the plan to cavalier Vito Cecinelli, the prison manager:

it was absolutely identical to the one Alfred

Dreyfus occuped on Devil's Island since 1895 and which would

have still occupied until 1906. In the cell previously had been

buried alive Pietro Acciarito, the failed murderer of Umberto

I in 1897, before being taken in 1904 to the Asylum for Insane

Criminals of Montelupo Fiorentino, where he ended his days in

1943.

The cell was slightly smaller than common ones, and measured 3

x 3 metres: the only furnishings consisted in a wooden bed with

a horsehair mattress (which during the day had to be lifted and

tied to the wall with big leather belts), a stool fixed to the

floor, a wooden washbowl, and the usual bucket.

The cell was separated from the others, the cells on the two sides

were taken up by the guards, and was placed at the end of a corridor

built between the offices and the depots. Even the terrace for

the exercise hour was isolated, so that the prisoner was kept

away also when his confinement was attenuated. The terrace was

the only point where his jailmates could theoretically see Bresci,

but his exercise hour coincided with a moment in which his fellow

prisoners were locked up: indeed they understood that Bresci had

died just because their daily interdiction to go out during that

hour ended (Mariani). On the terrace also two sentry-boxes were placed for the

two guards who watched him in every moment.

On May 18th, inspector Alessandro Doria reached

Santo Stefano, visited the prison, and ordered the director to

prevent the prisoner from having available a low stool, since

he could sit on the ground and lean his back against the bed,

to forbid him to keep a handkerchief and wearing cotton sweaters,

as well as buying bars of soap. He was also forbidden to write

or receive letters from his partner Sophie. (Galzerano, 2001, pag. 799)

Bresci had his feet

chained and wore the uniform with a black collar, distinguishing

lifers convicted of the most serious crimes, while the other inmates

had a yellow collar. His daily meals consisted of a soup without

meat and a loaf of bread. In addition he could buy groceries at

the shop, but he did so rarely: out of the sixty liras deposited

at the administration (sent from America by his wife) he spent

less than ten. (Centini)

Even in Santo Stefano

Bresci showed a calm behavior, and accepted the visit of the prison

chaplain, Father Antonio Fasulo,

but only to get some books. He received a copy of the Bible, and

one of the “Lives of the Fathers”, which he did

not appreciate, and therefore also required the Cormon and Manni

French-Italian vocabulary, who was found open and crinkled in

his cell when his dead body was officially discovered. Bresci

also had at his disposal the monthly bulletin of the "Rivista

di disciplina carceraria" ("Prison Discipline

Journal"), conceived for the education of prisoners,

containing edifying, moral and patriotic tales, the fourth and

last book available in the small penitentiary library. (Zucca)

The death

The registry office

of Santo Stefano Royal Penitentiary recorded the death of prisoner

"Gaetano Bresci son of the late Gaspero, sentenced to

life imprisonment for the murder of the king of Italy at Monza".

Gaetano Bresci was thirty-two years old.

The gaoler Antonio Barbieri maintained he had found Gaetano Bresci

dead at 3:00 PM on Wednesday May 22nd, 1901, after ten months of imprisonment.

At 2:45 PM Barbieri had seen Bresci alive, reading close to the

cell window. According to the official version Bresci would have

strangled himself with a towel or a handkerchief (according to

two versions, both official), hanging to the window bars, dodging

the continuous peephole surveillance, while the watchman at 2:50PM

had been away for a few minutes for physical needs, and without

making any noise, despite having his feet locked in a long chain,

fastened to a cell wall, which clinked at the slightest movement

of the prisoner. The two guards Barbieri and De Maria were suspended

from the service.

The second jailer, Giovanni De Maria, according to the official

version was sleeping, and rushed at the call of Barbieri, together

with the detainee Leonardo Tamorria, a blacksmith from Partinico

(province of Palermo), who was free to go around inside the prison,

since he handled general services. From the prison register it

appears that the last inspection had been carried out at 9:30AM

and the last check of the bars at 1:10PM.

According to the Anarchist journal “Rivista

Anarchica” the first official version, which referred

to a towel, was changed, when it was learnt that inmates were

not allowed to keep towels in the cell, so they switched to a

handkerchief, which anyway had to be large enough to hang oneself.

Other versions refer to a tablecloth (nobody knows where it might

come from, since Bresci neither had a table in his cell), to a

necktie (it is unclear how a prisoner could get such a garment),

tied to the towel, or to the livery collar or the trousers of

the prison uniform cut into strips and knotted to make a rope.

It doesn't seem that these objects have been found in the cell,

on the contrary the prison doctor Francesco Russolillo, at the

first examination of the corpse noticed that he wore the uniform

with white and hazel stripes, and the pants were intact. Therefore

there's a strong and grounded suspect that Bresci was murdered,

maybe in a date previous to that officially declared.

The French weekly journal Le Petit Journal in a short

article on June 9th, 1901 issue attributed the suicide to the desperate

conditions of detention in isolation, and to solve the problem

of the dodging of surveillance, hypothesizes that the jailers

had voluntarily left Bresci to act, for humanitarian reasons,

allowing him to put an end to his suffering. Another French weekly

journal L'Assiette au beurre of June 6th,

1901 represents instead on its cover

the hanged corpse of Bresci watched by a guard, a priest and a

bourgeois wearing a top hat, and at the bottom of the page a comment

by Vittorio Emanuele III : " it's the best that could

happen ".

Gaetano Bresci, as usual, had left aside for dinner a part of

his daily food ration, that he received in the morning, a soup

without meat with vegetables and pasta, and some grey bread, which

does not make one think of a person on the point of committing

suicide.

The prison doctor, Francesco Russolillo, who reported seeing the

corpse of Bresci immediately after it was found, still with the

"rope" around his neck, tells the typical framework

of the death by strangulation. The anarchist Amilcare Cipriani,

in the past detained for eight years in the penitentiary, deemed

the hypothesis of suicide completely impossible, both for the

continuous surveillance and because no prisoner could have handkerchiefs,

towels or any other piece of cloth suitable for making a rope,

furthermore lacking a support to which it could be hooked.

Some coincidences, when confirmed, could strengthen the thesis

of a state murder: the Director General of Prisons Doria was promoted

two months after Bresci's death and would have profited a redoubling

of his salary (increasing from 4,500 to 9,500 liras a year). The

anarchist prisoner Ezio Taddei, reported the story of an old lifer,

according to which Bresci was strangled by an inmate, head-scullion

Sanna, who two days after Bresci's death, was transferred to Procida

and then freed by the grant of Sovereign Pardon, perhaps as a

reward for the homicide. (Galzerano, 2001, pag. 855)

The late President of the Italian Republic Sandro

Pertini, in a speech of November 19th,

1947 to the Constituent Assembly said: "... I speak for

personal experience (...). In jail, Honourable Minister, it happens

this: a prisoner is struck; in consequence of the blows the prisoner

dies, and then everybody worries, and not only the jailers who

stroke the prisoner worry, but also the director, the doctor,

the chaplain and all the prison crew do it. And then they make

this: they lay the prisoner bare, they hang him to the window's

grating and they let him be found hanging this way. The doctor

comes and draws up a medical report of suicide. This was the end

of Bresci. Bresci has been struck to death, then they hung his

corpse to the window's grating of his cell at Santo Stefano, where

I have been a year and half".

Ugoberto Alfassio Grimaldi, quoting testimonies of political prisoners,

writes of Bresci: "That May 22nd

three guards made him the "Santantonio": that is covering

somebody with blankets and sheets and then beating him until his

death; his corpse had been buried, in a place of which remained

no trace in Santo Stefano archives, by two lifers who were sent

purposely there from an other jail, and then immediately away;

the penitentiary's commander had been promoted and the three jailers

had been rewarded".

From the private documents of the former Prime Minister Francesco

Crispi, it seems that already on May 18th,

four days before the "official" date of the death, a

representative of the government was in Santo Stefano, the aforementioned

inspector Alessandro Doria. For this visit the prison manager

asked the ministry whether should he allow Doria to see Bresci.

Furthermore, on May 24th, two days after "official"

death, the doctors who performed post-mortem examination found

the body in an advanced stage of decomposition. According to the

testimony of an ex-jailer, Bresci was killed no less than fifteen

days before, on May 7th, so that a journalist who witnessed

his burial reported that the body had a strong rotting smell.

(Rivista

Anarchica; Galzerano, 2001, pag. 843)

The corpse of Bresci underwent post-mortem examination by four

medical examiners, including professor Corrado, holder of forensic

medicine chair at the University of Naples and doctors Gianturco

and De Crecchio. There is no trace left of the detailed report

drafted by the doctors. (Galzerano, 2001, pag. 818)

The Italian-American anarchist newspaper L'Aurora of June

8th, 1901 (supplement to No. 34) imagines (or

narrates?) that King Vittorio Emanuele III went incognito to Santo

Stefano to ask Bresci to account for the murder of his father

Umberto, that the anarchist's response had been disdainful, and

the prison guards strangled Bresci in his own cell (Galzerano, 2001,

pag. 845-848)

Gaetano Bresci shared

with other prisoners the fate of being murdered by those who had

to safeguard him. Among the others Costantino Quaglieri, murdered

in Regina Coeli jail in Rome in

1894 (see my webpage

on him), Romeo Frezzi, murdered in

San Michele a Ripa jail in Rome in

1897 (see my webpage on him),

the young Communist from Calabria Rocco

Pugliese, murdered like Bresci in Santo Stefano in 1930 (see

my webpage on him), and

the anarchic railwayman Giuseppe Pinelli,

thrown from a window of Milan central police station on December

16th, 1969, a hundred years and a month after

Gaetano Bresci's birth, and never

forgotten.

After

the murder

From the jail's register,

which described life and death of any prisoner, a page is missing,

bearing the number 515, corresponding to Bresci's matriculation

number. Even in the Central State Archive

in Rome nothing can be found about Bresci. According to Arrigo

Petacco (1929-2018), the author of a successful biography

of Bresci, even the contents of a file disappeared, which, between

the "secret papers" of the Prime Minister Giolitti,

included the unofficial documentation on Bresci's death.

Bresci's body was buried on May 26th, 1901 in Santo Stefano cemetary.

According to unofficial sources, all his things were thrown along

with him in the grave. According to other sources, instead, Bresci's

body was thrown in the sea how the Naples' newspaper Il Mattino

wished for in an editorial signed "Vagus".

(Galzerano,

2001, pag. 837)

The journalist and

gastronome Luigi Veronelli (1926-2004)

engaged himself in the quest of Bresci's grave, and drew a plan

of the cemetery's burials, starting from hints he found on the

graves, including those of the confinees of the fascist era, which,

like the most ancient ones, did not bear indications. In september

1964 Veronelli pinpointed a cross bearing a scroll: "Gaetano

Bresci 22 May, 1901" (ParmaDaily, Galzerano, 2001,

pag. 821).

Just a relic of the

anarchist's imprisonment was left, his prison cap: it was marked

with the number 515, and it was kept in the small penitentiary

museum together with the cap of another famous anarchist, Pietro

Acciarito, who also tried to kill Umberto in 1897. Both caps were

lost during a prisoners' riot broken out in Santo Stefano in November

1943.

In the Criminal

museum in Rome other objects

sequestrated to Bresci after his arrest are kept: the revolver

he used to kill king Umberto I, a camera, chemical baths for photographic

processing and two suitcases containing personal belongings.

Memory

On July 29th

of each year, starting from 1901,

the anarchists remembered Monza regicide and the figure of Gaetano

Bresci, with special issues of newspapers and booklets, produced

outside Italy, in areas where communities of Italian emigrants

settled, like the United States, Brazil, Argentina, France and

Switzerland. The publications, beyond being widespread locally,

were also sent or introduced illegally in Italy, addressed to

the anarchists of the native land.

Many of the commemorative texts had in common a feeling of disapproval

of the Italian people, who had not seized the opportunity of regicide

to rebel and overthrow an anti-popular and liberticide regime.

In honour of the anarchist from Prato the christian name of Bresci

Thompson (1908-2004) was given, an U.S: painter and sculptor born

in Manhattan and then moved to Chelsea.

On July 27th, 1947 the Lombard anarchist federation

organized a demonstration in memory of Gaetano Bresci at the Cinema

Astra in Monza, in via Manzoni (see the photo

of the current modern building which lies there) attended by a

thousand people. At the end a plaque

was discovered, amidst "a jubilation of anarchist flags",

a few tens of meters from the "Expiatory Chapel". The

following day the police headquarters in Milan removed and seized

the plaque. (link).

In 1971 the film critic and screenwriter Tullio

Kezich (1928-2009) published the theatrical work “W Bresci: storia italiana in due

tempi”, ("Hooray for Bresci: Italian history

in two acts"), defined by the author as "grotesque

psychodrama" which staged the historical events that

led to the regicide of Monza, from the rejoicing of the Savoy

court and the top military officials for the repression of the

Milan riots to the echoes of a possible coup promoted by the same

circles of the court and the ruling classes, to the slavishness

of the press and of a theatrical company trying to stage the regicide,

without upsetting the censorship, at the trial which lasted a

day without leaving any chance to the defense. Kezich describes

Vittorio Emanuele III as an opportunist who tries not to end up

like his father with a wary and less violent policy, in contrast

with his mother Margherita, advocate of a reactionary response.

Kezich comes to the conclusion that all kings must be killed in

people's hearts and minds, eradicating the faith in the principle

of authority.

In 2002, on the occasion of the return to Italy of the male members

of the Savoia family, after the removal of the ban provided for

by the Italian Constitution, in Prato a writing appeared on a

wall: "The Savoya are coming back ... Gaetano's comrades

… too" (Borsini).

On July 29th, 2004, in the 104th

anniversary of the regicide, the Turin anarchists covered

Umberto's monument up, lying on Superga hill, in Turin, and affixed

a plaque in memory of Gaetano Bresci.

In the city of Carrara, heart of Italian anarchism, on May 2nd,

1988 a monument to Bresci was

inaugurated, made by the artist Sergio Signori. The work, unfinished

for the death of the artist, rises in Turigliano, in the gardens

in front of the cemetery, dedicated

to Gaetano Bresci, and was made under commission of the anarchist

craftsman Ugo Mazzucchelli.

Several actors and musicians have remembered the sacrifice of

Gaetano Bresci (see the links at the bottom of the page).

In close proximity of the Royal Expiatory Chapel built in Monza

on the exact place of the regicide, two graffiti celebrating Bresci

can be seen, one on the access lane

and one on the enclosure wall.

Currently it seems that only one

road has been dedicated to

Gaetano Bresci in Italy, exactly in Prato, his birthplace,

not far from Coiano, the hamlet in which his native home lies.

The city council of Prato led by the mayor Lohengrin Landini on

July 1st, 1976, decided to name a street

after Bresci: “it seems worthy of mention for reasons

related to the Italian history of the early twentieth century

and the meaning that in this context assumes the figure of this

Prato citizen" and furthermore: "In a historical

evaluation, his memory relies on the recognition that the act

he performed led to a turning point in Italian politics in the

social field, after the bloody and reactionary repressions that

had followed the African war and the riots of 1898".

The resolution was unanimously voted by the 38 participating councilors

(Mazzone). Conversely in Prato, no street

has been dedicated to the kings or other members of the House

of Savoia (Santin

and Riccomini).

On the island of Ventotene, the breakwater that protects the new

harbour is covered with murals, among which two represent Gaetano

Bresci, one with the sentence:

"I only appeal to the forthcoming Revolution"

pronounced by the anarchist during the trial, and the the

other facing the nearby island of Santo Stefano.

Bibliographic

reference:

-

AFFORTUNATI Alessandro (2015) Fedeli alle libere idee : il movimento

anarchico pratese dalle origini alla Resistenza. Zero in condotta,

Milano,

- ALFASSIO GRIMALDI Ugoberto (1970) Il re "buono". Feltrinelli,

Milan, Italy. p. 468-470.

- ANATRA Bruno (1972) Voce "Bresci Gaetano" In

Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani - Volume 14. link

- ANGIOLINI

Alfredo (1899-1900) Socialismo e socialisti in Italia. G. Nerbini,

Firenze.

- ANSALDO Giovanni (2010) Gli anarchici della Belle Époque.

Le Lettere, Firenze.

- ARUFFO Alessandro (2010) Gli anarchici italiani 1870-1970. Datanews,

Roma.

- BENTHAM Jeremy (1787) Panopticon, or the Inspection-house.

link

- BORSINI Edoardo (2006) Obiettivo “il re buono”. Microstoria

n- 8 n. 45 (gennaio- febbraio 2006) p 18-19.

- CECCHINI Bianca Maria (2011) Il re, l'assassino. L'Italia dal

1861 al regicidio di Umberto I di Savoia. Sala delle Conferenze

della Croce Verde., Pietrasanta, Lucca, Italy link

- CENTINI Massimo (2009) Come gli altruisti divennero terroristi.

Gli anarchici secondo Lombroso. Storia in Rete, January 2009:

54-55 link

- CERRITO Gino (1977) Dall'insurrezionalismo alla settimana rossa

: per una storia dell'anarchismo in Italia, 1881-1914. Crescita

politica, Firenze.

- CIPRIANI Amilcare (1900) Bresci e Savoia : il regicidio. Tipografia

della Questione sociale, Paterson, N.J., USA.

- DA PASSANO Mario (2005) Il «delitto di Regina Cœli».

Diritto e Storia, n.4 - In memoriam - Da Passano link

- DE JACO Aldo (editor) (1971) Gli anarchici. Cronaca inedita

dell’Unità d’Italia. Editori Riuniti, Roma.

- DEL CARRIA Renzo (1977) Proletari senza rivoluzione - vol.II

(1892-1914). Savelli, Rome, Italy. p.138.

- DELL'ERBA Nunzio (1983) Giornali e gruppi anarchici in Italia

: (1892-1900). Franco Angeli Editore, Milano.

- E.B. (1971) 29 luglio 1900. Rivista anarchica, anno

1 nr. 6 Summer 1971 link

- FASANELLA

Giovanni, GRIPPO Antonella (2012) Intrighi d'Italia. Sperling

& Kupfer, Milan, Italy, p. 161-187.

- FELDBAUER Sergio (1969) Attentati anarchici dell'ottocento.

Mondadori, Milano.

- FELISATTI Massimo (1975) Un delitto della polizia? Morte dell’anarchico

Romeo Frezzi, Bompiani,Milan, Italy,

- FERRARIS Luigi Vittorio (1968) L’assassinio di Umberto

I e gli anarchici di Paterson. Rassegna storica del Risorgimento,

LV (1968) p. 47-64.

- FIORELLI Dino (1976) Fermenti popolari e classe dirigente a

Prato: dalla caduta di Crispi all'armistizio del 1918. Bechi,

Prato, p 27-36.

- FONTANA Carlo (1971) Perché venne inscenato il “suicidio”

di Bresci. (intervista a U. Alfassio Grimaldi). Avanti,

13/03/1971, p. 3.

- GALZERANO Giuseppe (2001) Gaetano Bresci : la vita, l'attentato,

il processo e la morte del regicida anarchico. Galzerano editore

-Atti e memorie del popolo - Casalvelino Scalo - Salerno, Italy.

phone/fax: +39.0974.62028 e-mail: galzeranoeditore@tiscali.it

-

GALZERANO Giuseppe (2013) Gaetanina, la figlia del regicida. Il

Manifesto, 28/9/2013 link

- GIULIETTI Fabrizio (2017) Storia degli anarchici italiani in

età giolittiana. Angeli, Milano.

- GIUSTI Nazareno (2010) L'anarchico Bresci e Ponte all'Ania.

Il Giornale di Barga e della Valle del Serchio, 28/06/2010.

link

- GRUPPI ANARCHICI RIUNITI (G.A.R.) (1981) 29 luglio 1900. La

Cooperativa Tipolitografica, Carrara.

- HUNT Thomas (2016) Wrongly Executed? - The Long-forgotten Context

of Charles Sberna's 1939 Electrocution. Seven.Seven.Eight,

Whiting, Vermont, USA.

- KEZICH Tullio (1977) W Bresci: storia italiana in due

tempi. Bulzoni, Roma.

- LISANTI Francesco (2014) Apologia di Gaetano Bresci. Booktime,

Milano.

- LOMBARDO Mario (1974) in "Colloqui coi lettori" -

Storia Illustrata n. 194 - January 1974, p. 6

- MACIOCCO Giovanna Patrizia (2004) "Ill.mo Signor Sindaco

e Componenti il Consiglio Comunale .." Alfabetismo e scolarità

tra domanda privata e offerta pubblica: Prato, 1841-1911. Tesi

di dottorato di ricerca in storia, Istituto Universitario Europeo,

Firenze. Dipartimento di Storia e Civilizzazione Anno accademico

2003 - 2004, 15 ottobre 2004. link

- MARIANI Giuseppe (1954) Nel mondo degli ergastoli, S.n.,

Turin, Italy

- MARZI Paolo (2016) Gaetano Bresci, un regicida nella Valle del

Serchio. paolomarzi.blogspot.com, November 1st, 2016. link

- MASINI Pier Carlo (1981) Storia degli anarchici italiani nell'epoca

degli attentati. Rizzoli, Milano.

- MAZZONE Stefania (2018) Seta e anarchia: teorie e prassi degli

anarchici italiani a Paterson. Rubbettino, Soveria Mannelli.

- MEONI Alessandro (1969) Uno che passerà alla storia.

”Prato, Storia e Arte”, n. 26, dicembre 1969,

p. 7-22.

- MONTANARI Fabrizio (2013) Ernestina e Gaetano Bresci. 24Emilia,

link

- MOUY (Vicomte de) Roger (1901) La mort de Bresci à Santo-Stefano.

L'illustration, 3041, 8 Juin 1901, p. 371

- ORTALLI Massimo (2011) Gaetano Bresci, tessitore, anarchico

e uccisore di re. Nova Delphi, Roma.

- PASI Paolo (2017) Ho ucciso un principio. Eléuthera,

Milano.

- PERTINI Sandro (1947) in "Atti dell’Assemblea Costituente.

Discussioni", IX, November 19th, 1947, 2179-2180.

- PETACCO Arrigo (2001) L'anarchico che venne dall'America. Mondadori,

Milan, Italy.

- PETACCO Arrigo (1973) "I terroristi fanno tremare i re"

- Storia Illustrata n. 191 - October 1973, p. 64.

- POGGI Roberto (2018) Gaetano Bresci e l'inafferrabile "biondino".

Storia in Network. part 1 link. part 2 link.

- PUGLIESE Amelia (?) Viaggio nella casa di correzione penale

di Santo Stefano. http://www.ventotenet.org/tourinfo/santostefano.htm and http://www.ecn.org/filiarmonici/santostefano.html..

- RICCOMINI Marco (1983) Gaetano Bresci. Il tessitore anarchico.

”Prato, Storia e Arte”, n. 24, n. 63 dicembre

1983 p 33-35

- ROSADA Maria Grazia (1975) Gaetano Bresci. In “Il movimento

operaio italiano” edited by Franco Andreucci and Tommaso

Detti vol I A-Cec Editori riuniti, Rome, p 400-402.

- SACCHETTI Giorgio (2000) 29 luglio 1900 Gaetano Bresci da Coiano.

Microstoria, n. 2 n.12 (giugno-luglio 2000) p 10-11.

- SANTIN Fabio, RICCOMINI Marco (2006) Gaetano Bresci: un tessitore

anarchico. Mir edizioni, Montespertoli.

- SCERESINI Andrea (2020) Il mio album di famiglia con regicida.

La Repubblica, June 3rd, 2020, p. 30-31.

- SILIPO Cesare Gildo (1998) Un re: Umberto, un generale: Bava

Beccaris Fiorenzo, un anarchico: Gaetano Bresci. Il Centro

della copia, Milano.

- TOGLIATTI Palmiro (1922) Due date. Il comunista, 17 agosto

1922. In Palmiro Togliatti – Opere – a cura di Ernesto

Ragionieri – vol I – 1917-1926 Editori Riuniti, Roma,

1974, pp 399-402.

- TOSCANO Alfonso () Chi fu il terrore della "mano nera"

? link

- VAGHEGGI Paolo (1990) A Gaetano Bresci, gli anarchici'. In piazza

la statua contestata. La Repubblica, May 4th, 1990, sez. Cronaca,

p. 21.

- VALERA Paolo (1966). I cannoni di Bava Beccaris. Giordano,

Milano.

- VALERA Paolo (2010) L’assalto al convento. Il Muro di