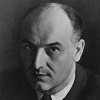

Rocco Pugliese was a young

militant of the Communist Party of Italy (see his portrait

and photo), from the Italian

region of Calabria. In 1930 he was assassinated by the fascist

jailers in the penitentiary

of Santo Stefano island, in

Pontine archipelago, where he had been deported as a result of

the fascist "special court" sentence in 1928.

Rocco was born on January 27th 1903 in Palmi, in the province

of Reggio Calabria, from Giuseppe Pugliese and Maria Polimeni,

and since his earliest age he was a Socialist Party militant,

being in 1921 amongst the founders

of the Palmi cell of Communist Party

of Italy, recently founded,

becoming then its secretary at the age of eighteen.

Rocco had a decisive revolutionary political training during his

the required military service, performed in Turin, a working-class

city, where the revolutionary movement was very strong and active.

The military service period was a proper school for executive

cadres, and the young man who came back to Palmi after being discharged

was a mature and conscious Communist executive (Pugliese L.).

In 1925, the year of the facts which led him to be a victim of

the fascist murderers, Rocco was a student of accounting. In città

Rocco era conosciuto anche con i soprannomi di .In the town Rocco

was also known by the nicknames of "Chiacchiarella"

("chatty") and "Mussuni" ("big

face"). (Bongiorno)

The premises

for Palmi events

Palmi, a town of southern Italy, in the

region Calabria, at that time had about 15,000 inhabitants (today

counts 19,000), it was a red stronghold, center of an intense

socialist and later communist political activity in a territory

with large estates (mainly citrus and olive plantations) with

a heavy exploitation of day labourers' manpower (Pugliese L.). The Palmi Socialist Party cell was established

soon after the devastating earthquake of Messina and Reggio Calabria

of December 28th 1908, which caused victims and

damages in the town. The Socialist Party Youth Club had 80 members,

and 78 of them voted in 1921 for the communist motion. (Bongiorno)

One of the most significant battle of the revolutionary movement

in Palmi was the winning one against the unreasonable rent imposed

by Palmi municipality to the people who dwelled the hovels built

for the homeless after the earthquake, and left in use for twenty

years, until 1928. (Pugliese

L.)

On June 27th, 1924 to protest the assassination

of the Socialist member of parliament Giacomo

Matteotti, the General Confederation of Labor proclaimed a

symbolic strike of ten minutes, which the Communist Party invited

to extend throughout the day, as happened in Palmi (Bongiorno), where it remained memorable

the march, when five thousand anti-fascists paraded reaching then

the town cemetary to lay wreaths and flowers (Spezzano, 1975).

The strong anti-fascist presence in Palmi made it the target of

violent assaults by fascist gangs, particularly numerous, since

Palmi fighters fasces (the fascist party cell) was one of the

first to be founded in the province of Reggio Calabria.

On November 4th, 1920, the second anniversary

of the victory in the World War I, a group of fascists, which

included two mafiosi, hired by the fascists to oppose the left,

one of whom was the convict Santo Scidone, attacked the Chamber

of Labor of Palmi, devastating it. (Bongiorno)

In the elections of April 6th, 1924, the Communists presented

one of their candidates, the lawyer Diomede Marvasi, in the college

of Palmi. Two evenings before the elections the Communists were

putting up their electoral posters when they were harassed by

a team of mafia headed by Scidone, and Rocco Pugliese came up

to them with a gun in his hand, started talking to the attackers

and convinced them to desist from provocation. (Bongiorno)

Marvasi came very close to being elected: he obtained 929 votes,

missing the quorum for a short delay, in return Fausto Gullo was

elected. (Bongiorno) The party cell counted three

hundred members, and one hundred and eighty were the members of

the juvenile circle, being mainly peasants and labourers, besides

professionals and students.

The strength of the anti-fascist movement in Palmi manifested

itself in a continuous contrast to the expansion of the emerging

regime, as when the fascist top dog Michele Bianchi was twice

prevented from giving a speech in Palmi, causing a short circuit

on the power grid and pushing him first to to stop outside the

city and then to to give up the event for safety reasons. (Pugliese L.,

Bongiorno)

In 1923 the leader of the fascist squads, Roberto Farinacci, came

to Palmi to defend in the Court of Assizes the fascists accused

for a clash that took place in Maropati, a town 35 km from Palmi,

where the fascists had murdered the mayor's brother while a rich

financier of the squads had been killed (Bongiorno).

In view of the Labor Day of May 1st, 1925, on the night between 29th

and 30th April, to prevent the celebrations,

ten anti-fascist leaders were arrested on pretexts, among them

Giuseppe Florio, and the brothers Giuseppe

and Antonino Bongiorno. These

latter shouted conventional yells in the street while the police

arrested them, and in this way Rocco Pugliese and Giuseppe Marafioti,

who lived near them, managed to slip away. (Bongiorno)

The reaction was a general strike, held on 2nd

and 3rd May, with street demonstrations

that had a so big attendance, that the authorities did not dare

to counter them. The fascists planned to disrupt the protest by

attacking the communist section, but the Palmese communists, led

by Rocco Pugliese, prevented them by devastating the local headquarters

of the fascist party, destroying the insulting cartels against

the strikers and slapping the fascists and forcing them to keep

off the town. (Bongiorno,

Pugliese L.)

On 20th

July in Palmi the feast of Sant'Elia Profeta was celebrated, with

traditional jaunts and songs and dances on the mountain of the

same name. The young communists of the city gathered to sing socialist

anthems, but were the target of the aggression of the fascist

Francesco Saffioti, who fired a shot at the group, without hitting

anyone. Chased through the woods, Saffioti managed to escape,

but the same night the police arrested thirteen communists for

attempted murder, in the person of Saffioti himself. After thirteen

days in prison, the arrested were released, without even being

questioned, thanks to the numerous testimonies that cleared them.

(Bongiorno)

On August 15th of the same year a squadron of

fascists from neighbouring villages camped in the night at the

gates of the town, near the Agricultural Institute, to attack

and set fire to the shacks of the leaders of the left parties

of Palmi, but they were put on the run by a hundred men, led by

Rocco and Giuseppe Pugliese and Antonino Bongiorno, who broke

into the fascist camp. Rocco ordered the leader of the fascists

to leave Palmi immediately, otherwise they would have been attacked,

and the fascists accomplished. (Bongiorno)

The ground which caused the events of August 30th,

1925 were the repeated humiliations suffered by the fascists in

Palmi, all the more harsh since they endorsed an ideology based

on arrogance and overman ideology, while in many other parts of

Italy Fascist gangs dominated uncontested.

The events

of the Varia

On August 27th, 1925 the religious celebrations

of the Virgin of the Letter

began in the town, with the traditional festivity of the Varia,

a great votive chariot symbolizing the

Assumption, dragged in procession by 200-300 faithfuls (the "mbuttaturi")

in the streets of the town, with the accompaniment of the band

(since 2013 the feast, together with three other similar Italian

celebrations, is inscribed in UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage

of Humanity, see link).

In 1925 the fascists imposed that during the festivity the Frigento

band, one out of two involved in the feast, played their anthem

"Giovinezza" (meaning "youth"), and

the (fascist) president of the celebration commitee, supported

this abuse.

The fascists wanted then to impose their anthem was played also

during the procession, instead of the traditional march composed

by Rosario Jonata, and the Palmi people rebelled to this overbearingness,

requiring the restitution of the contributions payed and boycotting

the transport of the Varia, considering also that the bearers

by tradition belonged to the five corporations: carters, sailors,

butchers, artisans and farmers, who mainly were Communist and

Socialist.

The leftist militants, first of all Rocco Pugliese, engaged in

a capillary work of persuasion to push the porters to boycott

the transport. (Bongiorno)

Actually just five

sailors and five carters offered themselves for the transport

of the chariot, and the procession, turned into a fascist political

parade, was boycotted even by the priests: indeed just one of

them took part in the procession. The fascists were forced to

improvise bearers to complete the procession. (Bongiorno)

The fascist gangs' provocations went on, even with insults and

threats to left-wing militants in the streets of Palmi, and the

tension reached its maximum at midnight of August 30th,

while the town population was gathering in the main square, piazza

Vittorio Emanuele, currently piazza

1° maggio, to watch the fireworks. Antonino Bongiorno,

Rocco Pugliese and Giuseppe Marafioti also were going to see the

launch of balloons in praise of the Soviet revolution, which they

had made prepare. (Bongiorno)

The fascists burst into the De Rosa café, which lied besides

the fascist party headquarters, but whose tables were as usual

crowded by Communists and Socialists, insulting them and starting

to sing once more "Giovinezza". Rocco Pugliese

summoned to stop provocation, beginning to sing the Communist

anthem “Bandiera Rossa" (Red Flag), but he was

assaulted with a stick by the fascist Rocco Gerocarni and reacted

throwing him a chair. During the brawl some gunshots were fired,

and two fascists were wounded: Rocco Gerocarni, that died the

following day, and Rosario Privitera, besides to two passers-by

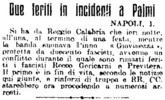

(see the news on the Communist

Party's newspaper "l'Unità"

of September 2nd 1925 and the fictional

version of the official Press Agency Stefani, drawn by the

Turin newspaper "La Stampa" of September 1st,

1925).

According to the author Leonida Repaci (see below) who was a witness

of the events, the actual target of the shots was he himself,

who was scratched by two bullets, while the third one killed Gerocarni.

The shots were fired from above to below from the terrace of Sambiase

family, facing the café, by the same fascists, who by mistake

shot their companion Gerocarni. The motive of the ambush should

be included in the framework of the sudden rise of violence by

the hard-liner wing of fascism, leaded by the fascist beaters'

boss Farinacci, in order to break the deadlock in which Mussolini

had fallen after Matteotti's murder and the consequent reactions

by the antifascists. The target of Palmi assault was anyway a

town with steady antifascist principles, who was therefore punished

for its refuse to submit to fascist hooligan's violence.

The reaction of the recent fascist regimen was very tough: a real

manhunt began and the police commissioner Francesco Cavalieri

arrested many antifascists of the region, accusing them of organizing

a subversive conspiracy; the same Cavalieri later admitted, during

the trial, that the arrests were due to political reasons instead

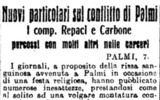

to the homicide (see the news on "l'Unità"

of September 8th, 1925).

Farinacci sent a telegram spurring them to the revenge ("I

can assure you that fascist blood shedding these days will be

avenged in due time") (Bongiorno) and

the September 15th the fascist gangs devastated

the circle "Unione e Progresso" and the house

of the communist laborer Managò, who was later arrested

by the police. The fascists also assaulted the house of Leonida

Repaci's brother where they stole objects and money, and tried

to burst into the Palmi jail, in order to lynch the antifascists

arrested for the Varia events. According to Antonino Bongiorno

and Leonida Repaci, a prisoner linked to the mafia, a certain

Giovanni Campanella, allegedly foiled the fascist assault, perhaps

out of a desire for personal redemption, dissuading the fascists,

also thanks to large quantities of weapons hidden in the prison.

(Bongiorno)

The journalist Giuseppe Dato, correspondent of the newspaper "Gazzetta

di Messina e delle Calabrie", even being a fascist too,

was assaulted and thrown in a basin full of water, because he

had criticized in a correspondence the fascist gangs' violences.

In the following days the fascists impeached, as a matter of fact,

the access to everybody they didn't agree, including the prisoners'

lawyers (see "l'Unità"

of September 15th 1925).

The "trial"

The dead of Gerocarni

was attributed to the communists as a preconception and preliminary

investigation was conducted in an extremely partial way: many

witnesses who had given depositions for the prosecution, retracted,

reporting they had been threatened by the fascists. In the same

year, in October, two of the witnesses killed themselves, and

one of them left a message explaining his suicide was due to the

remorse for wrongly accusing Leonida Repaci, Giuseppe Pugliese

and Giuseppe Marazzita, but the court did not consider this.

Some of the accusations brought against the anti-fascists were

grotesque: a witness, a certain Giuseppe Vizzari, claimed "to

have recognized the brothers Bongiorno, Carbone and Marazzita

by the flames of their guns". Even the victim, Rocco

Gerocarni, was among the witnesses: despite being dying he would

have indicated the names of five shooters, all Communists, including

Rocco Pugliese. It later turned out that he would only nod his

head when one of them was named, perhaps aided by someone holding

his head with his hand. (Bongiorno)

On December 5th, 1925 Barone Ferrara, the Attorney

general by the Court of Appeal of Catanzaro, asked to commit thirty-one

persons to trial for complicity in premeditated homicide and missed

premeditated homicide. The prosecution section of the Court of

Appeal of Catanzaro on March 29th, 1926 committed 15 persons to

trial by the Court of Assizes of Palmi, while the others were

acquitted with the formula of "not guilty" or on the

grounds of insufficient evidence, like in the case of Leonida

Repaci (see "l'Unità"

of April 3rd, 1926).

The trial began on October 26th, 1926 at 9:30pm by the Court

of Assizes of Nicastro, where it was remitted for legitimate suspicion.

With an abuse that anticipated the future management of justice

by the part of the fascist regimen, three out of four defence

attorneys appointed by the communist defendants, Francesco Lo

Sardo, Fausto Gullo and Ezio Riboldi, all Members of the Parliament,

were arrested and sent to the confinement, while Nicola Zupo alone

remained in the defense (Bongiorno);

on November 30th, 1926 the trial was then remitted

since the Attorney general asked to commit four witnesses to trial

because they retracted their accusatory depositions. In the same

year 1926, following the attack of the fifteen-years-old Anteo

Zamboni, who tried to kill Mussolini, with the emergency laws

of November 26th 1926 the special

court for the defence of the State was established. The name

of "court" was absolutely unjustified, inasmuch as it

was not constituted by judges, but rather by militants of the

fascist party, and in particular by consuls of the MVSN (National

Security Voluntary Militia).

On March 12th 1928 the Court of Cassation declared

with a sentence that the process had to be assigned to the special

court, where the November 27th

of the same year the

trial began. The fifteen antifascist defendants, who had spent

more than three years in preventive imprisonment, were charged

of "homicide, attempted murder, actions aimed to stir

a civil war up, insurrection against the State".

Between the defendants there was Rocco Pugliese, who had before

the court a not at all submissive behaviour, coherently with his

intransigence in the antifascist struggle. Public Prosecutor Isgrò

defined the defendants as "the group of communists who,

led by Rocco Pugliese, in the square of Palmi, on the evening

of August 30, shot" (Bongiorno)

and asked for Rocco Pugliese for a life imprisonment, for other

eight defendants the term of imprisonment proposed was of 30 years,

while the "lighter" sentence asked was of 12 years,

and for just one defendant the acquittal on the grounds of insufficient

evidence was asked. Death penalty had been abolished in Italy

in 1889 (de facto since 1877) and was restored by the fascist

regime in 1930.

On December 5th, 1928, at 8:30pm, just eight

days after the beginning of the trial, the court (President Antonino Tringali Casanuova, rapporteur

Presti), issued Sentence No 145, that inflicted very tough convictions:

the heaviest, of 24 years and 7 months, was received just by Rocco

Pugliese, while Natale Borgese and Vincenzo Pugliese were sentenced

to 10 years and 8 months, Giuseppe Florio and Gregorio Grasso

to 10 years and 7 months, Giuseppe and Antonino Bongiorno to 8

years and 7 months. This latter was tried again by the special

court in 1935, for organization and participation to the Communist

Party, and was sentenced to 12 years more.

The sentence of Rocco was the hardest issued by the special court

up to that moment, except for those against Gino Lucetti and Tito

Zaniboni, who had tried to kill the duce. (Bongiorno)

The others six antifascists were acquitted, between them Francesco

Carbone, Antonio Sambiase, Giuseppe Pugliese, Pasquale Carella

and Giuseppe de Salvo, besides the Socialist lawyer Giuseppe Marazzita,

which years after was elected in the Senate of the Republic, which

anyway was repeatedy imprisoned in the remaining years of the

fascist dictature.

It must also remember that Fortunato, Rocco's elder brother, born

on May 7th, 1891, cabman by trade, married

with eight children, was arrested on November 30th,

1926 for demonstrating solidarity with Rocco, and was assigned

to confinement in Lampedusa and then to Ustica island. Despite

the death of a daughter and although he was suffering of exuding

trachoma that made him nearly blind, he was kept in detention

and released only in March 1929.

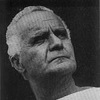

The Repaci

affair

Another antifascist

of Palmi involved in the events of the Varia was Leonida

Rèpaci (1898-1985), writer and later on also painter,

who conceived the Viareggio Literary Prize and was a lawyer too.

According to Francesco Spezzano, senator of the Communist Party

in the post-war period, was the real target, with Rocco Pugliese,

of the punitive expedition of the fascist gang.

Repaci was emprisoned but, as previously mentioned, was then acquitted

during the preliminary investigation and wasn't submitted to the

special Court. His acquittal, like that of other defendant, was

attributed to interventions of men of position, in the case of

Repaci to that of Arnaldo Mussolini, brother of the "duce",

besides the counsel for the defence constituted by big shots of

the regimen. In any case Repaci benefitted of numerous witnessings

of personages well agreed to the fascist regimen. His elder brother

Gaetano was moreover Mussolini's family physician.

While Rèpaci was in jail wrote "In fondo al pozzo"

("In the bottom of the well"), a novel with many autobiographic

references, even to the Varia events of 1925.

Anyway Repaci, after some more than a month after his acquittal,

resigned from the Communist Party with a letter,

published by the Party's newspaper "l'Unità"

on May 6th 1926, in which he claimed his

political position was marginal and sideward to that of the Party

and announced his own return to privacy. Repaci wrote. "The

latest painful events in Palmi (...) force me, for the necessities

of life that unfortunately we must live every day, for that minimum

of peace that I owe to my troubled spirit and above all for a

promise made to my mother in front of the his bed of pain, to

ask you for complete freedom of action towards the Party in whose

ranks I always held a place as a loner and as an artist. (...)

today, as I leave your ranks to take refuge totally in myself

and attend to my art, welcome my heartfelt greetings dear friends".

L'Unità answered the letter

of Repaci in a very polemic way, with an unisigned article, although

attribuited to Antonio Gramsci, which

compared Repaci's calling himself out to the suffering of the

communist political prisoners who didn't renounce their own political

choices. L'Unità wrote : "Alas, it is not easy

for a petty-bourgeois intellectual to pass through the fire of

workers' ideology and communist discipline!" and about

the letter: "The workers will read it with interest, but

they must not be saddened beyond the limit marked by the consideration

of a man who did not have the courage to follow them in the very

difficult path of the class struggle". It seems that

the reply infuriated Repaci, who threatened to challenge Gramsci

to a duel, who replied to accept the duel, but adopting potatoes

as a weapon. (Bongiorno)

The controversy continued also in 1944, after the liberation of

Rome, between "l'Unità" and the reactionary

newspaper "Il Tempo". On "l'Unità"

the editor Celeste Negarville and

Lucio Lombardo Radice reminded

Repaci of the way in which he had been acquitted by the special

fascist court, by intervention of the regime, and Repaci defended

himself on "Il Tempo" with violent insults, trying

to pass the attacks on him as attacks on the freedom of the press.

(Bongiorno)

At this point, "l'Unità" published a letter from

Antonino and Giuseppe Bongiorno which reported many facts that

confirmed the interventions in its favor by big shots of the regime.

At first Repaci denied its authenticity, stating that the Bongiorno

brothers could not have been in Rome, and indeed it ssemed to

him that they were dead. However, when the two brothers visited

him at the newspaper's seat, Repaci dropped the controversy, and

published a very brief acknowledgment of the visit by the two

Bongiornos. (Bongiorno)

The murder

Rocco Pugliese was

secluded on January 19th, 1929 in Santo Stefano penitentiary

(see my webpage on it) which

was used by the fascist regimen in order to deport the more dangerous

opposers, with the purpose of bending their will with the hardest

conditions of detainment. The political prisoners sentenced by

the special court were afflicted by a particularly hard treatment,

with the isolation from the common prisoners, in order to avoid

that their charisma could have grip on them. They were also submitted

to a more stringent surveillance, urged to the jailers with a

notice fixed to their cell's doors, warning: "dangerous

prisoner to be carefully guarded".

Rocco was locked in the fourth section, those of the "incorrigibles"

created experimentally, and named "teratocomium", that

is monsters' shelter, where the political prisoners most dangerous

for the fascism were imprisoned. (Bongiorno)

In Santo Stefano Rocco maintained his fierce behaviour ("an

exemple of resistance and pride", according to Vico Faggi),

and refused to submit himself to the fascist jail machine, that

made him pay dearly, at first with continuous vexations and tortures,

and finally with the dead, which occurred on October 17th,

1930.

According to the official version Pugliese commited suicide hanging

himself, while another version, poorly credible, maintains he

died suffocated while two jailers tried to force-feed him with

a probe, while he was tied in restraints at his bed. The force-feeding

would have been decided as a result of a supposed hunger strike

of Rocco.

In reality several affordable sources maintain that Pugliese was

strangled or hit to death by the jailers: according to Francesco

Spezzano "after having thrown a blanket on his head (...)

they beated him to death" and moreover "his desperate

screams were heard for long by his companions of imprisonment

(...) that, locked in the other cells, couldn't do anything to

help him" and then "the emotion for the barbarous

murder was enormous between the prisoners who made a collection

to send a wreath to his funeral".

The above described treatment was called by the guards the "Sant'Antonio",

with a term derived from the Naples mafia slang: it consisted

in bursting unexpectedly in the cell, covering the victim with

a blanket, and then hitting him hardly with kicks, punchs, cudgels

or with the heavy cell's keys. The blanket was used in order to

allow the aggressors not to be recognized, to suffocate the screams

of the victims and impeach them to react, and also for not leaving

traces on the body of the target of the beating, that could testify

about the aggression. According to the Ligurian anarchist Giuseppe

Mariani, once imprisoned in Santo Stefano, in the penitentiary

during the beatings the blanket was not used, since the guards,

being certain of their impunity, didn't think they need any precaution.

According to Mariani the "Santantonio" against Rocco

was performed by guard corporal Barbara and by sickroom warden

Giacobbo, by command of head guard Luigi Porta, in the utmost

indifference of penitentiary's manager Russo, who was there.

The communist Giovanni Pianezza, cellmate of Rocco, obtained the

permission to keep watch beside the corpse in the mortuary, declaring

to be his cousin. In a moment of inattention of the guards succeeded

to to raise the sheet that covered the body and saw the face was

leaden, like for a death for asphyxia. Taken by surprise by the

guards, he was threatened to die in the same way of Rocco, if

he had spoken, and then he was immediately transferred.

The socialist leader Sandro Pertini, who was president of the

Italian Republic from 1978 to 1985, was secluded in Santo Stefano

from 1929 to 1930, and many years later, in 1947, once elected

deputy of the Constituent Assembly, reminded in a speech before

the assembly that "Rocco Pugliese was dispatched in the

prison of Santo Stefano when I was there, in restraints".

The speech of Pertini was a reply to the answer given by the Minister

of Justice Giuseppe Grassi to a question he made about the thrashing

made by the jailers of some prisoners of Poggioreale jail in Naples,

followed by the death of one of them.

Pertini was very clear: "... I speak for personal experience

(...). In jail, Honourable Minister, it happens this: a prisoner

is struck; in consequence of the blows the prisoner dies, and

then everybody worries, and not only the jailers who stroke the

prisoner worry, but also the director, the doctor, the chaplain

and all the prison crew do it. And then they make this: they lay

the prisoner bare, they hang him to the window's grating and they

let him be found hanging this way. The doctor comes and he draws

up a medical report of suicide. This was the end of Bresci. Bresci

has been struck to death, then they hung the corpse to the window's

grating of his cell at Santo Stefano, where I have been a year

and half".

Pertini referred to the death of Gaetano

Bresci, the anarchist from Prato, near Florence, sentenced

to life imprisonment for the murder of the king Umberto I (see

my webpage about him), but died in

1901, after few months from his transfer to Santo Stefano.

Ugoberto Alfassio Grimaldi, quoting testimonies of political prisoners,

writes of Bresci: "That May 22nd

three guards made him the "Santantonio": that is covering

somebody with blankets and sheets and then beating him until his

death; his corpse had been buried, in a place of which remained

no trace in Santo Stefano archives, by two lifers who were sent

purposely there from an other jail, and then immediately away;

the penitentiary's commander had been promoted and the three jailers

had been rewarded".

The communist Girolamo Li Causi,

later senator of the Republic, wrote in his autobiography: "The

news that Pugliese himself had died caused me great pain. Our

companion, suffering from the mistreatment and abuse to which

he was subjected, had decided to go on hunger strike: in an attempt

to force him to gulp down the food, the custody only succeeded

in strangling him. He was a great fighter, full of vitality and

spirit of sacrifice; another comrade leaving ...".

Moreover Pertini, in a testimony reported in a book edited by

Vico Faggi, relates: "One night I was awaken by a choked

cry «mummy, mummy!». The day after somebody spread

the rumour that Rocco Pugliese hanged himself; but the suicide

was nothing more than an act. Pugliese had been killed by the

jailers."

In the same work is reminded that the murder of political prisoners

in the fascist jails wasn't un uncommon case, how testified by

the cases of Gastone Sozzi in

Perugia jail and Romolo Tranquilli,

the brother of the writer Ignazio Silone, in Procida jail. The

January 1st , 1929 clandestine edition of

l'Unità reported the

names of Communist prisoner dead or anyway sick in the fascist

jails.

Rocco's death was immediately perceived as a murder and the news

came to the anti-Fascist circles in Italy and in exile. The French

Communist Party's newspaper "L'Humanité"

published on December 21st, 1930 an article

by Gabriel Péri,

who was later a Communist member of parliament and a victim of

the Nazis, entitled: "Comment périrent à

San Stefano les communistes Castellano et Pugliesi" ("How

the Communist militants Castellano and Pugliesi died in Santo

Stefano") (Pugliese

L.), which denounced

the death of two Communist prisoners, Castellano and Rocco Pugliese,

(erroneously referred to as "Pugliesi"), and the serious

health condition of the communist militant Emmanuelli and of Sandro

Pertini, ill with tuberculosis. The article attributed the death

of Rocco to a reprisal by the guards for refusing their sexual

advances, shouting instead aloud to fight them off. Later Rocco

would have been harassed by providing him uneatable food, which

he refused, triggering segregation and fasting at the "enclosure

bed", with subsequent death.

Péri's article and the spread of the news by the exiled

antifascists embarassed the fascist regime, and Mussolini established

a farcical commission of inquiry into the conditions of inmates

in prisons, chaired by the Deputy Attorney General Claudio Rizzo,

who already on January 19th concluded his work by writing

: "at the beginning of last October (...), together with

a more notable state of organic decay, a real form of psychopathy

began to manifest itself in Mr. Pugliese, manifested in violent

excesses and in a characteristic delirium of persecution, which

led him to consider any food poisoned, and therefore to refuse

to ingest it (...). On October 12th,

he was hospitalized in the sick bay, diagnosed with strophobia,

persecution mania, apical phlegm, T.B. and cardiac neurosis, and,

by prescription from the doctor, he had to be secured to the enclosure

bed and subjected to artificial nutrition." On October 15th,

according to the report, the director of the penitentiary proposed

the transfer of Rocco to the criminalal asylum in Naples, which

could not happen because "the prisoner died of cardiac

paralysis in the afternoon of the 17th". (Bongiorno). The commission predictably gave

no results, except for a temporary alleviation of the brutish

prison treatment.

Rocco's family knew of his death almost by chance and the corpse

was never given back.

(Cordova,

1965) The police headquarters in Reggio

Calabria took measures to prevent Rocco's funeral from generating

demonstrations against the regime and gave instructions for the

funeral "not to take place in public form and for the

body to be transported overnight from the Palmi railway station

to the cemetery", but actually Rocco's body never arrived

in Palmi and it was probably destroyed in Santo Stefano (Bongiorno, Pugliese

L.) like probably

it happened to Gaetano Bresci's body.

A theatrical

work and six books

The theatrical company

Teatridelsud of Palmi staged a play called "L’Arrobbafumu"

a work by Francesco Suriano, interpreted by Peppino

Mazzotta, taken by a book by

the same author, taking a hint from the events of Palmi to tell

about the Calabria and its delays of development.

The Calabrian writer Domenico Gangemi

published in 2004 a novel freely inspired from the events of the

Varia of 1925 entitled "'25 nero",

published by Pellegrini Editore. Besides Natale Pace, a moderate

representative and deputy mayor of Palmi, in his essay "Il

debito" ("The Debt"), published in 2006 by Laruffa

Editore, tells Rocco's vicissitude from the point of view of Leonida

Repaci, who was a close friend with the author.

In 2008 Giuseppe (Pino) Bongiorno,

son of Antonino, published the book "Una

vita da comunista" ("A life as a Communist")

for the publisher L'Albatros of Rome, dedicated to the life of

his father, which gives wide room to the events of the Varia of

1925 and to the legal proceedings of his father, of Rocco and

of all the other defendants.

In 2015 the publisher Annales of Rome edited "Rocco

Pugliese: un Comunista di Calabria" a nice book by

Lorenzo Pugliese, a relative

of Rocco, which reports with passion and involvement the outcome

of a 18 years research, performed by the author through archives,

journals, libraries and witnesses' stories. This book entirely

fulfils Sandro Pertini's wish, expressed to a Rocco's niece, so

that the sacrifice of this young man from Palmi was never forgotten.

In 2017, the journalist Pier Vittorio

Buffa issued the book "Non volevo

morire così" ("I didn't want to die

like this"), published by Nutrimenti of Rome, which tells

the stories of Santo Stefano prisoners and Ventotene confinees,

collected largely from their dossiers kept in the archives, including

those of Santo Stefano. A chapter is dedicated to Rocco Pugliese.

The city of Palmi named a street

after Rocco Pugliese and on April 25th, 2018 placed a plaque

in viale Rimembranze, 20, in the place where his house once stood:

For everlasting memory, here

stood the native home of

Rocco Pugliese 1903-1930.

A Palmese Communist who with other young antifascists established

the cell of the Communist Party of Italy in Palmi.

Innocent and Condemned by the Special Court for the "facts

of the Varia" of 30th August, 1925 killed by the Fascist brutality

in Santo Stefano Penitentiary.

"One night I was awaken by a choked cry «mummy,

mummy!». The day after somebody spread the rumour that Rocco

Pugliese hanged himself; but the suicide was nothing more than

an act. Pugliese had been killed by the jailers."

Sandro Pertini.

THE CITY PLACED

Palmi April 25th, 2018.

Rocco

Pugliese nowadays

In spite of his seclusion,

murder and concealment of his corpse, though more than ninety

years went by from his death and maybe noone of those who knew

Rocco is still alive, that 27 years old young man from Calabria

is still living in memory, his sacrifice still arouses gratitude

and his brutal murder still inspires horror and indignation.

BIBLIOGRAPHIC

REFERENCES:

-

ALFASSIO GRIMALDI Ugoberto (1970) Il re "buono". Feltrinelli,

Milano. Pag. 468-470.

- AJELLO Nello (2003) Il confino. Ecco le vacanze che offriva

il duce. La Repubblica, 13 settembre 2003, pag. 39.

- AMENDOLA Eva Paola (2006) Storia fotografica del Partito Comunista

Italiano. Editori Riuniti, Roma.

- BONGIORNO Pino (2008) Una vita da comunista. Biografia di Antonino

Bongiorno. L'Albatros, Roma.

- BUFFA Pier Vittorio (2017) No volevo morire così. Nutrimenti,

Roma. Pag. 87-94.

- CORDOVA Ferdinando (1965) Il processo Gerocarni. Historica,

16 (18): 196-212.

- CORDOVA Ferdinando (1977) Alle origini del PCI in Calabria -

1918-1926. Bulzoni, Roma.

- CORDOVA Ferdinando (1994) Un originale documento sui fatti di

Palmi dell'estate del 1925, Historica, XLVII-4, pag. 157-167.

- DA PASSANO Mario Il «delitto di Regina Cœli»

(link)

- DAL PONT Adriano (1975) I lager di Mussolini. La Pietra,

Milano.

- DAL PONT Adriano, LEONETTI Alfonso, MAIELLO Pasquale, ZOCCHI

Lino (1962) Aula 4: tutti i processi del Tribunale speciale fascista.

ANPPIA, Roma.

- FAGGI Vico (edited by) (1970) Sandro Pertini: sei condanne due

evasioni. Mondadori, Milano.

- GALZERANO Giuseppe (1988) Gaetano Bresci: la vita, l' attentato,

il processo e la morte del regicida anarchico. Galzerano editore

- Atti e memorie del popolo - Casalvelino Scalo (Salerno).

tel. and fax: +39.0974.62028 http://galzeranoeditore.blogspot.it/ e-mail: giuseppe.galzerano@tiscalinet.it

- GANGEMI Domenico (2004) '25 nero. Luigi Pellegrini Editore,

Cosenza.

- GHINI Celso, DAL PONT Adriano (1971) Antifascisti al confino

1926-1943. Editori Riuniti, Roma.

- LI CAUSI Girolamo (1974) Il lungo cammino : autobiografia 1906-1944.

Editori Riuniti, Roma. p. 151-152

- LISA Athos (1973) Memorie. In carcere con Gramsci. Feltrinelli,

Milano.

- MARIANI Giuseppe (1954) Nel mondo degli ergastoli, S.n.,

Torino..

- PACE Natale (2006) Il debito. Leonida Repaci nella storia. Laruffa

Editore, Reggio Calabria.

- PERTINI Sandro (1947) in "Atti dell’Assemblea Costituente.

Discussioni", IX, 19 novembre 1947, 2179-2180.

- PUGLIESE Amelia (s.a.) Viaggio nella casa di correzione penale

di Santo Stefano. http://www.ventotenet.org/tourinfo/santostefano.htm.

- PUGLIESE Lorenzo (2015) Rocco Pugliese: un Comunista di Calabria).

Annales, Roma. link

- SPEZZANO Francesco (1968) La lotta politica in Calabria: (1861-1925).

Lacaita, Manduria.

- SPEZZANO Francesco (1975) Fascismo e antifascismo in Calabria.

Lacaita, Manduria.

- SPEZZANO Francesco (1984) Item "Pugliese, Rocco" in

"Enciclopedia dell’antifascismo e della Resistenza".

La Pietra-Walk Over, Milano. IV: p. 813-814.

- SPRIANO Paolo (1969) Storia del Partito Comunista Italiano.

Einaudi, Torino.

WEB

REFERENCES (accessible

on: October 29th,2022):

http://www.ecn.org/filiarmonici/santostefano.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Palmi

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Leonida_Repaci

http://www.terreprotette.it/tp2/106

http://www.ventotene.it/escursioni.aspx

https://circoloarmino.files.wordpress.com/2014/04/antifascisti-nati-o-residenti-a-palmi.pdf

no longer

accessible on: October 29th,2022:

http://www.anpi.it/ts/1928_4trim.htm

http://www.variadipalmi.it/curiosita.asp?modulo=leggi&ID=6

http://spazioinwind.libero.it/nb/vittoriofoa/tribunale.htm

http://www.teatrodellacquario.com/stagioni/2007/schede/arrobbafumo.htm

http://www.variadipalmi.it/

http://www.marcellobotarelli.it/santostefano/index.htm

http://www.istoreco-re.it/isto/default.asp?id=326&lang=ITA

http://www.domenicogangemi.it/

http://www.traveleurope.it/ventoten.htm

Page

created on: March

1st, 2009 and last updated: November 22nd, 2022

Page

created on: March

1st, 2009 and last updated: November 22nd, 2022